Consider the following statements: “Dr Brown is treating my depression” and “I am seeing Dr Brown for my depression”

Illness commodified becomes something separate from the person – this thing we call ‘my depression’ implies that it is not me that is depressed, but a thing apart from ‘me’. We (Dr Brown and I) can then work out a treatment plan for this thing we call depression – Sertraline, CBT, some graded exercise and less alcohol.

I’ve been wondering what it means to be seeing Dr Brown for my depression.

I have had therapists. And I wouldn’t say that she’s my therapist. I was intrigued to discover that Sigmund Freud did not consider himself a therapist. In fact he deliberately chose not describe his work as psycho-therapy. The one time he visited the United States, it was at the time that the American Medical Association ruled that only qualified doctors could practice psychoanalysis and he feared that instead of exploring patients’ psyche they would attempt to diagnose and cure them. He never visited the US again.

Let’s not pretend for a moment that I wouldn’t be glad of a cure and to be rid of the depression that’s ruining my life and my relationships (or what’s left of them). I’ve got nothing against cures. I’m not so sure that I’m so interested in being diagnosed any more. Being told that I’m suffering with ‘depression’ or ‘anxiety’ or ‘panic attacks’ or that I have ‘chronic pain’ or a ‘borderline personality disorder’ hasn’t been especially helpful. Most diagnoses are tautologies – I’m depressed and anxious so I’m suffering from depression and anxiety. Being told that I’ve got a personality disorder was helpful only in so far as it made me question the whole diagnostic process. Does a diagnosis help me make sense of how I feel? Does it help me access the help I need to get better? Are diagnoses objective truths or historical artifacts?

I’ve been depressed for so long now that I wonder what would be left without my depression, but perhaps I’d settle for there just being less of it. Freud said something about wanting to help people shift from having a pathological, debilitating depression to an ordinary depression. Perhaps that would do.

Depression isn’t something I can fight. I’ve heard of people with cancer object to fighting talk and war metaphors; war on cancer, fighting back, being strong, winning the fight or giving up the fight, or being defeated by cancer. I’ve seen people almost killed by friendly fire in battles against cancer – hairless, bruised and bleeding, sepsis, diarrhoea and vomiting, dehydration and renal failure. And I’ve seen the same damage done in battles against depression – rendered fat, impotent, diabetic and zombiefied by the drugs, re-traumatised by therapy, brutalised by confinement. I think the problems are inherent in all types of healthcare, not just mental health.

The more I think about it, I cannot separate my depression from me – how ever much I’d like to. Perhaps there was a time, at the beginning. Maybe there is another me: less antisocial, less self-loathing, more worthwhile underneath this fog of depression. Waiting to come up for air. But now I’m not so sure. The depression and me have become one.

Validation

I do remember at some point thinking, ‘she believes me, she actually believes me!’. I don’t remember exactly when that was, but it was sometime in the beginning of 2018. The hard part was trusting her enough to believe her when she said that she believed me. Practically my whole life I’ve trusted people; from when I was a kid or too naïve or too vulnerable and they’ve taken advantage of me, until I couldn’t trust anyone any more. And this is what it has been like with doctors. You’re vulnerable, afraid, trying to get help, and they expect you to trust them. And I’m thinking, ‘yeah, right, where have I heard that before?’ And I can tell you exactly where I heard it before. And I can tell by their body language and the way they say it whether or not they mean it. And nine times out of ten they don’t. They’re saying it to get you to take the pills or stay in hospital, or sign the form or whatever.

It wasn’t easy to trust Dr Brown to begin with. There wasn’t a particular moment when I went from not trusting to trusting, but there was a time when I went from not trusting to trusting her enough.

Even now I worry about how much I can say. How much she can handle. I have to make a judgement about how busy or stressed she seems, I worry that she’s going to get fed up with me calling or won’t be able to handle how messed up I am. I remember an online group where I was been warned not to tell her about my fits I was having. The other people in the group said that’s a sure way your doctor will think you’re mad because they’re not real epileptic seizures. I did tell her one time, but only when she asked if I ever had them and we talked about a film she’d seen about people who had been abused that suffered from dissociative seizures afterwards. She seemed genuinely curious and not at all judgmental.

Vindication

If there’s a key to our relationship, I think that it’s the fact that she’s not judgmental, or rather she is judgmental but not in the way I’m used to. What I’m used to is being blamed – for everything; for everything I do and for everything about me. That’s how it’s been my whole life. I was born wrong, a mistake from conception. I’ve got personality disorders to prove it. “you know what?” she says, “It’s not your fault”. If I’m in the right frame of mind I want to give her a hug when she says that, but mostly I want to scream, “How. Do. You. Know? What can you possibly know about me that I don’t know?” There are things I’ve done and said and thought that she’ll never know, even if there are things she already knows about me that nobody else knows. There are thoughts that terrorise me in my nightmares and flashbacks that I’ve spent years trying to blank out with sex and drugs and booze and cutting and bingeing and the rest.

Carl Rogers came up with this idea of Unconditional Positive Regard – which means seeing the good in the other person. It’s like not being judged, so that no matter what you say or do, like when you’ve fallen off the wagon and gone on a bender we can agree that wasn’t such a good thing to do, but it doesn’t change who I am. It doesn’t alter the fact that underneath she still thinks I’m worth looking after again, and again and every other time I screw up. That’s why it’s unconditional and it’s positive because she thinks I’m worth it, and the ‘regard’ bit? Well that’s like presence.

Presence

There are times when I have screamed at Dr Brown. Perhaps not at full volume, but I’ve lost it. I know what Hilary Mantel meant when she said, The sufferer is in a state of high alertness and of anger looking for a cause. What strikes me is that (in my case anyway) anger comes before the pain: a wash of strong, predictive, irritation emotion that I don’t feel at any other time. What I remember is how calm my GP was. I need a doctor who can handle my pain, my anger and my losing it from time to time. Someone who doesn’t recoil and try to get rid of me with another prescription or a referral. Someone who can bear the fact that they don’t know the answer and they can’t fix me. Someone who can bear to be with me when they don’t know what to say and not fiddle irritatingly with their computer or launch into a long unsolicited explanation or piece of advice. I think that asking your GP to be present shouldn’t be too much to ask, but God knows it’s a rare and beautiful thing, because presence is what I need when I’m unbearable. That’s when I’ve been sectioned, sedated and restrained. It doesn’t make so much sense at the time, but I can see it now, thanks to Dr Brown. The times when I’ve hated her most are when she’s failed at that. When presence is what I needed, and she wasn’t there for me. The point is that it’s when I’m hardest to be around that I need her to be present and that’s what brings me back to earth.

The Good Enough Doctor

Donald Winnacot wrote about the Good Enough Mother in 1953. He was a jobbing paediatrician who saw thousands of mothers and babies as well as being a psychoanalist. He came to realise that babies and young children benefit when their mothers failed them in manageable ways. By these small failures of care-giving, these cracks in their mothers’ carapace of infallibility they realised that they could cope without them after all but that it wasn’t a total catastrophe if sometimes she wasn’t there. I know a lot of Dr Brown’s other patients. I can imagine what it’s like listening to them all day. No wonder she’s sometimes not so present after twelve hours at work. It’s good too, to realise that she’s a normal person which gives me hope that you don’t need to be a saint to put up with me.

Perhaps more simply, what I get from my GP is acceptance and commitment. Put like that it sounds a bit like I’ve got to put up with how I feel and with what I’ve got. Which is a bit disappointing. After all most people go to the doctor to get a cure or at least a bit of symptom relief. When I started seeing her that’s definitely what I was looking for. All my friends were telling me to go back and demand that if she couldn’t tell me what was wrong or fix my pain she should refer me to someone who could. I was hearing all these stories about people who got sick or died because their GPs didn’t refer them in time. I’m pretty sure she was offended, her professional pride dented. I thought she was saying it must be in my head because the blood tests didn’t show up anything. She even used a phrase later on – something about changing role from ‘tour-guide’ to ‘travel agent’ from care-giver to care-navigator. But I didn’t see it like that. Why couldn’t she be both? Why give up on caring for someone just because you’re referring them to a specialist? Why stop being there for someone just because someone else is there as well? She’s in my life for maybe 10 minutes a month these days and even at the height of my troubles, barely 20 minutes a week. Sometimes I think she needs to remember that. “There are too many of us for the likes of you” I told her one day. ‘You might think it’s all down to you, but it’s not’.

I don’t know how she does it sometimes. Working around here there’s a lot of mental illness, lots of drugs and alcohol, lots of arguing and fighting. Lots of people worse off than me. I’ve seen the receptionists get it in the neck something terrible too. What they have to put up with, it’s a wonder they haven’t chucked half the patients off the list. But I hope they’re getting looked after too, all of them. You can’t look after other people if you’re not being looked after yourself. If there’s one thing she’s taught me it’s that. I’ve always found that the hardest thing. And I worry it’s the same for her too.

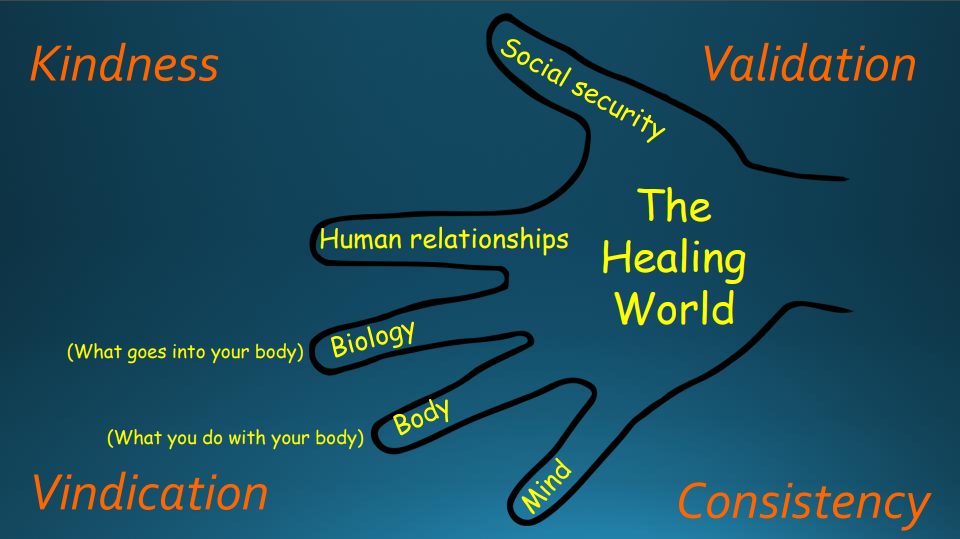

The Healing World and The Trauma World

Thank you for the honesty of this.

Interesting.The universal need for ‘God’ which lands at the door of the medical practitioner… but s/he are different, and s/he is a human being like the others… and needs God (or a person like him/her) as much…

Have shared this with my trainee today for a tutorial discussion. Thank you so much for this very thoughtful piece of writing.

How did it go? My inspiration was a tutorial I had with a my ST1 trainee, a 5th year medical student and a patient on the subject of chronic pain. I’ve shared it with all of them too. Lots of people thought I was the patient, and some was personal, but it was also informed by the references and involvement with Balint groups. I’m giving a workshop on chronic pain via zoom for GPs in Manchester with the patient in December too