When I get sick, I want to be looked after by someone who enjoys their work, is motivated, up to date, and well supported. Someone whose work gives meaning and purpose to their life. I want someone who is driven by desire to look after me and make me better, who enjoys figuring out diagnostic dilemmas and sharing treatment options. I want someone who is interested in my illness and cares about me because healthcare is about people caring for people.

The biggest barrier to this kind of care, is demoralised, alienated healthcare staff.

The latest GMC (General Medical Council) State of Medical Education and Practice report published in June 2023 concluded that more doctors than ever are at risk of burnout, are considering leaving the profession, and have experienced compromised patient safety or care. I’m afraid that if I do get sick, I’ll be looked after by someone like this.

While it’s tempting to believe that there was a ‘golden era’ where NHS staff were overwhelmingly enthusiastic and caring, the reality is that healthcare professionals have rarely, if ever been treated in ways that fully enable them to give the best possible care to their patients.

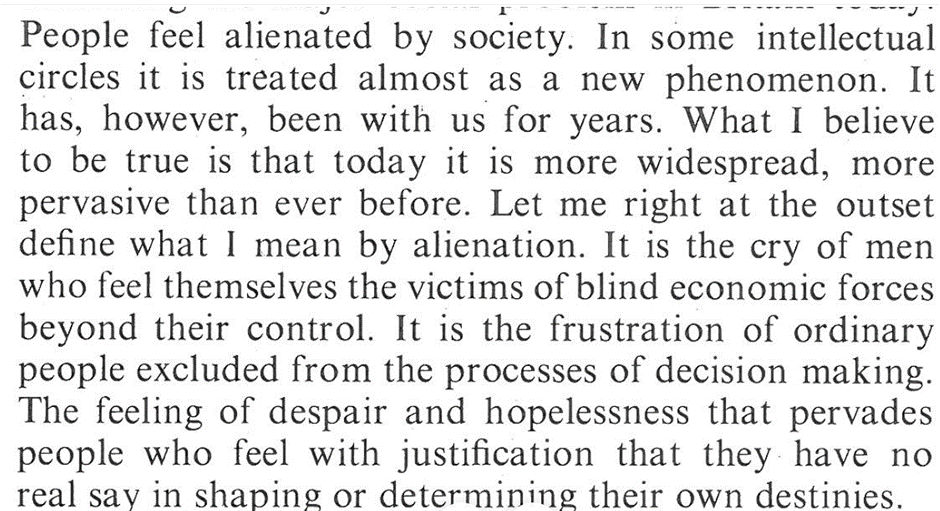

Long before the NHS began Karl Marx described four aspects of alienation that affected workers under industrial means of production: alienation from the process of labour; alienation from the products of labour; alienation from themselves and alienation from others. And in 1959 Isabel Menzies Lyth described attempts by managers and senior nurses to deal with burnout in nursing students that made the problems worse by further alienating the students in the ways that Marx described. In 2023 it seems clear to me that alienation is the problem affecting healthcare professionals in the NHS today, and attempts to deal with burnout and stress are making things worse in the same ways that Menzies Lyth observed over 60 years ago. I’ll focus on GPs for the reason that I’ve been a GP for over 20 years, but I think the problems apply to all doctors and many other healthcare professionals.

Alienation from the process of labour

The basic process of labour for a GP is a clinical consultation where I want to offer my full attention and presence to someone who may be overwhelmed by illness and stress. I want the organisation and IT to support this, so that I have enough time and we are uninterrupted, I have all the information I need and the tools of production – equipment, as well as access to investigations and clinical colleagues are all available, and the IT works perfectly, or at least adequately.

For Marx, alienation from the process of production meant that workers feel they lack control over the conditions of their work, and they are pressured to prove that they are being productive, with rewards for success or punishment for failure despite them having little or no autonomy. The reality for most GPs is that very frequently lack the time they need with patients, are frequently interrupted, and lack access to the tools they need (especially support). Instead of supporting them to do their work, the IT demands data entry above all else and seizes up or slows down all the time. We are judged and therefore paid, above all else according to efficient data entry.

According to Marx,

“The worker “[d]oes not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself;” The production content, direction and form are imposed by the capitalist. The worker is being controlled and told what to do since they do not own the means of production, they have no say in production, “labour is external to the worker, i.e. it does not belong to his essential being.”

The recent Commonwealth Fund report into General Practice showed that job satisfaction was lowest in the UK of all countries surveyed, especially with regards to workload, administrative burdens and time available to spend with patients.

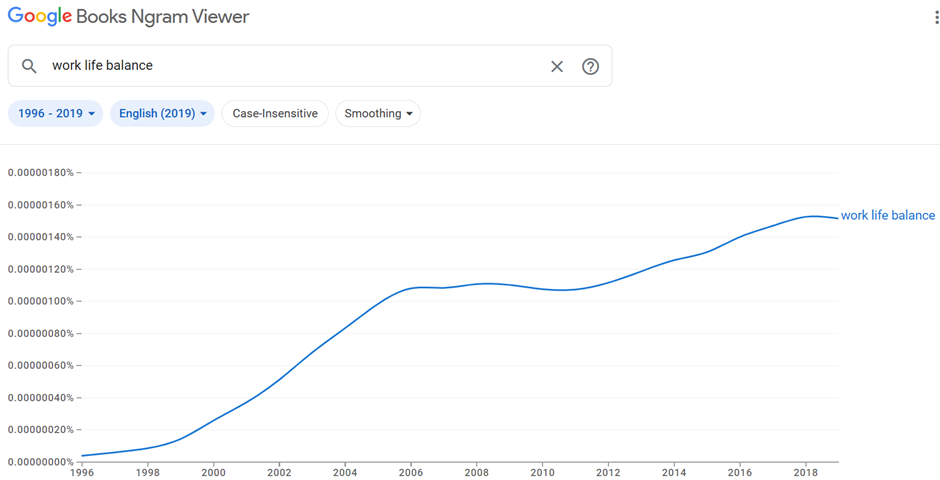

Lacking meaning, purpose and satisfaction in work, workers seek these things elsewhere. Many doctors are choosing ‘portfolio careers’ with only one role in the NHS and others in private medicine or other careers entirely. Doctors these days are told to consider their work-life balance as if work is not part of life, but something they are obliged to do in order to earn enough money to have a life elsewhere. I qualified as a doctor in 1996 and this is the rise in use of the term ‘work life balance’ according to Google.

When work has meaning and purpose and when workers have adequate degrees of autonomy, control and responsibility over their working conditions, then the issue of ‘work-life’ balance becomes less of an issue, because work is part of life.

Breaking down something complex and relational like a consultation into an opportunity for data entry is a form of ‘taskification’ described by Professor Alison Leary, in her excellent presentation for the Nuffield Trust (19.02). ‘Taskification’ is an aspect of industrialisation described by Taylor (1882-1911) Taylorism was a method for increasing the productivity of industrial work. Also known as scientific management Taylor broke work down into standardised tasks, with workers paid according to complexity, working at the top of their grade/ limit of their skills, with rewards for success and loss or punishment for failure. In healthcare jobs have been broken down into tasks which must be meticulously and repetitively documented. Tasks that are considered more straightforward are given to qualified, less well-paid people. There are now over 7000 different roles in the NHS forcing staff to spend more time working at the top of their grade while new roles take on work they used to do. When I started working as a GP, a ’pill check’ was a consultation where you met a woman to check her blood pressure and discuss how she was getting on with her contraceptive pill. ‘Pill check’ was shorthand for catching up in a clinic that was running late, recovering a little between consultations that were emotionally draining or clinically complex. Almost every consultation resembling a ‘pill check’ is now done by someone else, so we find ourselves doing more demanding work without respite.

Alongside our clinics full of complex patients GPs are responsible for everyone else that is seeing the patients that we used to see, like sick children. This is relatively simple in terms of clinical decision-making, but valuable and enjoyable work and gives GPs an opportunity to build relationships with young families. Often the supervision takes more time than it used to take when the GP saw the patient. As Spike Milligan joked in the 1990’s, “I’ve invented a machine that does the work of two men, but it takes three men to operate it!”

Taskification also describes the demands that the electronic medical record (EMR) places on clinical encounters. At one time a useful place to document my thoughts, the EMR has become a behemoth of dashboards and I have become a data-entry slave while my patients and colleagues are starved of my attention. Trying to find details about a patient’s life circumstances which are essential to make sense of symptoms and suffering is almost impossible among the pages of templates in which tasks are documented. Patients meet anonymous professionals who fill in checklists instead of caring professionals who can give their full attention.

In 1959, Isabel Menzies Lyth was asked to investigate a London teaching hospital where nearly 40% of student nurses were quitting before completing their training, a proportion not seen since, until very recently. She was writing at a time when professional knowledge was shrouded in secrecy, paternalism was unquestioned and external scrutiny was frowned upon. Sixty years later, Don Berwick, head of the Institute for Health Improvement, described this as Era1 for medicine. According to Berwick we have responded to this with Era 2- “A massive ravenous investment in tools of scrutiny and inspection and control, massive investment in contingency and massive under-investment in change and learning and innovation”

The collision of norms from these 2 eras—between the romance of professional autonomy on the one hand, and the various tools of external accountability on the other—leads to discomfort and self-protective reactions. Physicians, other clinicians, and many health care managers feel angry, misunderstood, and overcontrolled. Payers, governments, and consumer groups feel suspicious, resisted, and often helpless. Champions of era 1 circle the wagons to defend professional prerogatives. Champions of era 2 invest in more and more ravenous inspection and control.

https://qi.elft.nhs.uk/resource/era-3-for-medicine-and-healthcare/

There is little point telling health professionals, who are committed and conscientious, that they have nothing to fear from inspections. My own consulting room breaks all kinds of rules for having a hand-woven rug on the floor, plants on the shelves and edible products in the drawers. Nobody from CQC has ever inspected my patient interactions, my clinical supervision, or my open-door policy for students, trainees and colleagues.

Alienation from the products of labour

Alienation from the products of labour occurs when clinical staff are unable to relate to the results of their interventions on individual patients because their involvement is so brief, so partial, and they aren’t involved in follow up. For Marx, the worker should be able to see something of himself in the final product. An example of delayed gratification in this respect is a story told by a doctor in an episode of The Nocturnists podcast where Emergency Physician Mike Abernethy described the impact of meeting a patient whose life he saved thirty years before, while shopping in Walmart. Listening to it I sensed the alienation he felt from not knowing at the time of his involvement whether the child he had operated on had survived. Discovering that he had grown to be a healthy adult 30 years later, the emotional impact of feeling a sense of connection with the product of his labour is immense.

Having a relationship with the products of your labour – a patient who recovers or one who does less well is essential for learning as well as finding meaning and purpose in work. Being reduced to a cog in a machine is demoralising. GPs are paid for the quality and quantity of their data collection because this is easier to measure than the products of their labour – patients with healthier lives. Even surgeons whose relationship with the products of their labour is more straightforward are contractually sometimes unable to follow up their patients for long enough to know much if anything about the long-term impact of their work.

Alienation from ourselves

We are alienated from ourselves because the values that bought us into clinical practice and are part of our professional, caring identity are crushed or compromised by our experiences. Professor Jill Maben described the erosion of idealism among nursing students in 2007. Lacking the time or resources to make a difference or provide the care that we know their patients need, we suffer moral injury.

In 1959, Isabel Menzies Lyth described institutional ‘defences against anxiety’ which demoralised nurses in a London teaching hospital. They were given very little autonomy and not allowed to take responsibility even when they were capable. A risk averse culture meant that even trivial decisions had to be passed up to senior staff and everything had to be documented, often multiple times. The nurses came into their profession with ideals of caring and being cared for in a caring culture and discovered that this was almost impossible, and consequently they were overwhelmed and anxious. Management believed that their anxiety stemmed from having to deal with patients with serious illness who were sometimes dying and often in abject states – having to deal with the visceral reality of bodily fluids and infection and incurable disease. To ‘protect’ nurses from the emotional labour of their work, management and senior nurses broke up the relationships that developed from individual patient care so that nurses instead were responsible for tasks such as patient observations, medication rounds, admissions, discharges and so on. These decisions were misguided because emotionally demanding though the work was, it was what the student nurses had chosen to do. Rather than help them cope better with it by providing support, policies separated them from the meaningful aspects of their work. As a GP with interests in complex trauma and chronic pain, I know that, as Anatole Broyard wrote,

“Physicians have been taught in medical school that they must keep the patient at a distance because there isn’t time to accommodate his personality, or because if the doctor becomes involved in the patient’s predicament, the emotional burden will be too great. As I’ve suggested, it doesn’t take much time to make good contact, but beyond that the emotional burden of avoiding the patient may be much harder on the doctor than he imagines. It may be that this sometimes makes him complain of feeling harassed. A doctor’s job would be so much more interesting and satisfying if he simply let himself plunge into the patient, if he could lose his own fear of falling.”

One principle when helping patients cope with the aftermath of trauma is that attempts to escape the resulting hypervigilance, numbness and pain, shame and guilt, often through the use of alcohol or drugs, binge-eating or other addictive behaviour – does more harm than actually working with trauma’s physical and psychic wounds. Doctors who find themselves feeling overwhelmed by the impact of patient suffering need to be supported to lean in and have more effective therapeutic relationships rather than keeping their patients at arm’s length.

Alienation from others

In his latest book, The Distance Between Us, Darren McGarvey proposes that the major problem in Britain today is that the ruling class and the working classes are so alienated from one-another that they cannot possibly understand each other’s experiences, values, needs or motivations. Alienation from colleagues in healthcare also results from intensely busy shift work culture that makes it very difficult for colleagues to meet with each other to discuss their work or even get together and go out and relax after work. Shifts for junior doctors and GPs may be shorter than they used to be, but they are so pressured that there are very few opportunities to know what others are dealing with. We’re glued to our computers. Supervision becomes perfunctory and education becomes didact, “do this, don’t do that” rather than a thoughtful discussion. There’s no time for small talk, no checking in to see if colleagues are coping and few people have any capacity to lend a hand. People, specialties, departments and organisations defend their boundaries fiercely with referral protocols. Only half-jokingly do we say our patients are either too mad, not mad enough or the wrong kind of mad for any of the available mental health services. Online meetings have obliterated time spent travelling and eating together or sharing a coffee and catching up. Small talk, which has always been an invaluable way to share knowledge and support one’s colleagues is severely endangered.

Alienation is as much an issue today as it was when Marx described it in 1844 and when Menzies Lyth wrote about it in 1959.

In 1972, James Reid, rector of Glasgow university gave his inaugural address,

From alienation to connection.

The cure for alienation is connection, connection with the processes and outcomes of our work and connection with our colleagues and ourselves. We need the time, support and resources to do our work to the best of our ability, so we need to invest in more and better administrative support and IT that actually supports effective consultations. In Era 3 for medicine, Don Berwick calls for a 70% reduction in clinical admin over 5 years. This alone would improve retention of GPs above anything else. Connection with the outcomes of our labour requires organisations to focus on relational continuity and whole-person care so that GPs can learn alongside their patients about how illness interventions impact them over time. Connection with our colleagues needs to be valued and time for informal support as well as formal opportunities for supervision and education needs to be paid at the same rate as clinical duties. Connection with our ideals needs organisations and policy makers to understand what gives GPs meaning and purpose in their work and support this in every possible way or they will leave to work elsewhere or change career. In the immediate term, the biggest risk is that doctors will leave the most stressful work, which is, and has always been among patients experiencing the highest levels of deprivation. They will reduce their hours, or leave to work in less deprived areas, or overseas or to do private work. The Inverse Care Law states that the supply of healthcare is always inversely proportionate to the need for care, and more so wherever market forces influence the supply. As philosopher Michael Sandel warned, we have moved from a situation where market forces aren’t just used to shape the economy, but are used to influence everything in society, including healthcare.

Attention to alienation and connection could be the cure that the NHS needs.

As a former IT professional, so many of us have the same sense of alienation. It’s not that we want IT to slow down folks, or to be data entry, we want to make software that helps. I’m not from the UK but I wouldn’t be surprised if folks felt similarly in the UK.

We don’t get to decide much when it comes to designing a EHR. It’s some bigwig upwards. We might be lucky to have focus group discussions with stakeholders like yourself amd other medical staff, then government regulations for IT security comes into play… and everything gets really messy, bulky. Especially as medical software contains sensitive data and often has to transmit data into other medical systems.

Corporate decision maker folks often want a standardised software that can be pushed out to small clinics or large hospitals. Cheaply. It’s costly to customise but lovely when a medical setting has it.

There’s little room for truly catering to different medical settings, people’s preferred charting styles etc. Free text instead of extremely long drop down menus is the better option.

And yes I’ve heard my GPs over the years complain about IT and I tell them I wish I could make it better. 🙂

I’m nearly 40 and remember a time when you could walk into your gp surgery and wait in the waiting room to see the dr, reception would squeeze you in if they had a free moment. The Gp would also take as long as needed with you. You could call for an appointment the next day and that wasn’t even for an emergency.

A huge issue I think is the fact you never see the same GP twice. Not only is this unsettling for patients as we like continuity but also wastes the very small time allocated trying to go over old ground – back in the day the family dr would know the issue, he would know your families issues and this would save precious time not to mention the fact that by knowing previous issues/family issues the dr might be able to figure out the problem just based on that. I also feel a dr who regularly sees the same patients would most likely enjoy their job more. But the biggest concern I have is how can a dr ever learn without following something from symptoms to through to diagnosis and treatment. If dr a) gets to hear my symptoms, dr b) also gets to hear my symptoms, dr c) actions a referral, follow up after specialist or bloods is with dr d) – dr d is told of diagnosis and treatment plan – how is drs a,b, c or d ever supposed to learn for the next patient? Drs learn by experience and they aren’t getting a full experience which in turn means patients aren’t getting fully experienced drs.

When you have 1 gp and symptoms = x diagnosis and he follows you through to the end he now has that as a tool. The next person that comes in with the same symptoms he can now recognise a potential diagnosis.

Market forces and evolution of computers as a means to measure ‘productivity’ paved the way for the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in UK NHS General Practice. One of the key ‘whys?’ (the root causes) behind the introduction of QOF was lack of trust in GPs. The resulting alienation and loss of continuity and purpose can only be overcome by building connection and trust. Trust can only come from confident and fearless leadership and management – command and control infantilisation stems from obsession with budgets, reducing spending and increasing ‘productivity’ which ultimately can only pay lip service to outcomes and experiences for workers, patients and carers.