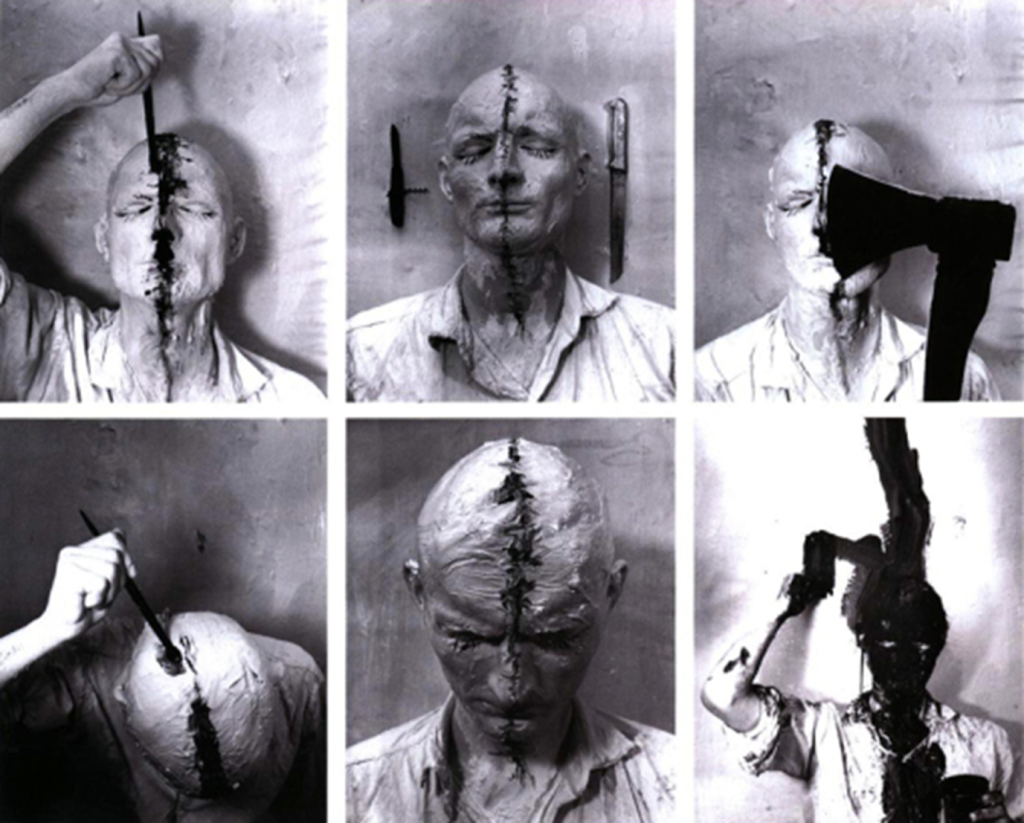

Suffering, Pain, and Anguish

John Berger distinguished pain from anguish, the latter was painful suffering, whilst the former reminds us of our powers of healing and recovery. Last year I cycled into a tree and fractured eleven ribs and my shoulder and punctured my lung. I knew what Berger meant, especially when he said that pain without anguish can reinforce a sense of invulnerability. I began to look forward to my rehabilitation almost as soon as arrived at hospital and last week I cycled past the tree I’d crashed into, defiantly, back to full fitness. Recently fingers on my right hand flared with my first painful episode of osteoarthritis, and I experienced anguish at this reminder of ageing and bodily decay. My fingers caused me more pain than the fractured ribs and shoulder had done.

Freud claimed that people fear death, the reality of having to live with other people, the indifference of the natural world, and the inevitability of bodily frailty and decay. Philosopher and psychiatrist Irvin Yalom said that people fear death, isolation, meaninglessness, and uncertainty. Fundamentally, we all know that existential fears are what make suffering so hard to bear, and yet medicine is strangely wedded to the utopian belief that suffering can be medicated or cut away.

After several years of neuroscientists claiming salience over interpretations of the mind, perhaps it is time to re-evaluate philosophical and psychoanalytical ideas about causes of and ways out of suffering.

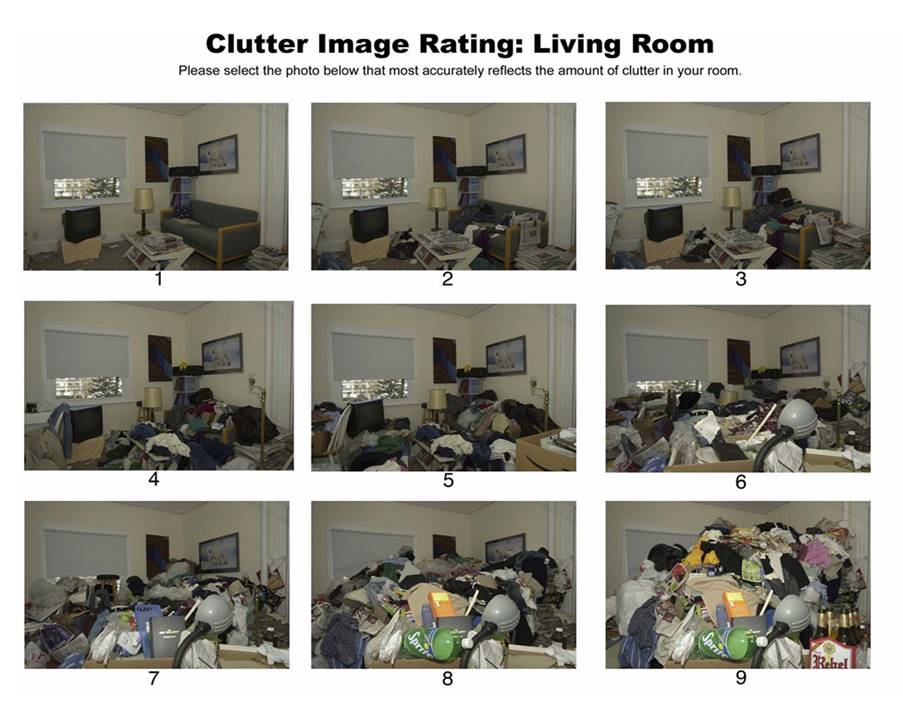

I have begun asking my patients whose physical pain or mental distress I cannot relieve, and they cannot bear, about existential suffering. Almost all of them greatly fear their bodies and the world around them and dread the uncertainty of not knowing if they will ever get better. Many of them cannot identify meaning or purpose when I ask them what gives them a reason to live, let alone happiness or joy. Most of them are socially isolated and struggle to cope with other people and fear being a burden, emotionally or physically. Few spend time in nature. The existential fears both precede and follow on from the mental and physical suffering. Illness amplifies anguish.

I think I’ve always known this but haven’t until recently been able to describe it and I’m still trying to figure out how to put it into practice.

Like Freud, I have witnessed in my consulting room over the last 25 years, that most people who suffer like this have endured significant adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) including sexual abuse, violence, and neglect. Many of them found ways of coping, often for decades, before ending up seeking help from a doctor, and even then, take a long while before disclosing their past traumas. It takes an average of twenty-six years for survivors of child sexual abuse to disclose. Like Freud, I am accustomed to people outside the consulting room contradicting my experiences and telling me that it’s much less to do with childhood experiences than I claim.

If only that were true.

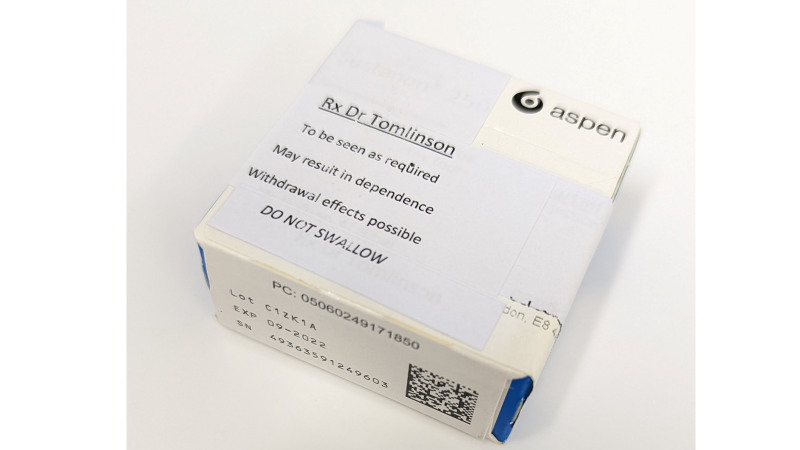

Faced with having to cope with shame and anguish many people shut themselves off from the world or try to numb the pain with intoxicants which is why addiction is so often a solution to a problem. Doctors become co-dependents and supply the obliviogenic pharmacopeia of opiods, benzodiazepines, psychotropics, and gabapentinoids their patients crave. Patients have high thresholds for pleasure and seek high-risk, high-stakes sexual, recreational, and employment activities, raising the bar and increasing the dose to get the same effects. Freud recommended substitution or sublimation – replacing Eros/ Thanatos, the libidinal and violent drives with lower intensity activities, like Voltaire’s Candide tending his garden. Becoming a Hermit was another of Freud’s suggestions, perhaps not entirely seriously, but monasteries and spiritual retreats are full of young people escaping lives of destructive hedonism. Artistic and scientific pursuits are recommended too, and while I have little experience, friends who are professional musicians, dancers, and artists affirm that their world is full of survivors who channel their suffering into their creative work. Is therapy the answer? Mark Solms, a neuroscientist, has written a book making the bold claim that psychotherapy is The Only Cure, but fails to acknowledge that it is practically impossible to find the right therapist at the right time, at the right price, for long enough to make a lasting difference.

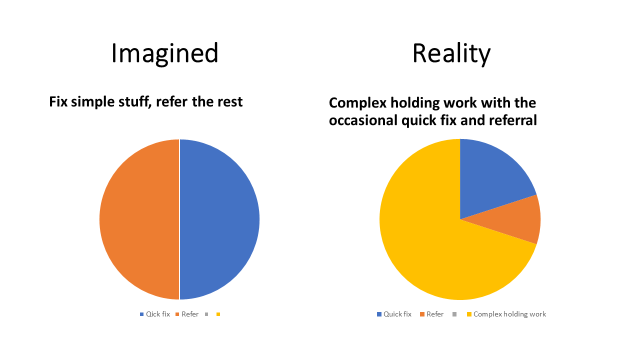

A GP, so long as they still care about continuity enough to make it achievable for their patients, can be the right person at the right time, for long enough, at no charge. We might protest that we’re not therapists, but perhaps, that’s inevitably the position we’re put in. People come to us with the acknowledgement that they don’t fully know their bodies or minds, and they want our help to understand them better. We can find plenty in Freud to disagree with, but it’s self-evident that it’s not just our anatomy and physiology that are out of sight and out of mind, but also a great many other things that drive our behaviour. Our conscious selves are not the only hands on the wheel. If therapy isn’t part of our skill set and or if we’re dogmatic about separating bodies and minds, the least we can do is adhere to the maxim ‘Primum non nocere’, first do no harm. Quaternary prevention* is preventing harm due to medical interventions. Failure to recognise the existential dimensions of suffering is a medical misdiagnosis and leads to the wrong treatment. Psychotherapist Gary Greenberg wrote about Freud’s attitude towards doctors,

In 1926, less than two decades after Freud’s visit, the doctors of the New York Psychoanalytic Society declared their independence from their European forebears by decreeing that only physicians could practice psychoanalysis. Back in Vienna, Freud was livid. Medical education was exactly the wrong preparation for a psychoanalyst, he wrote, as it abandoned study of “the history of civilization and sociology” for anatomy and biology, culture for science. A psychoanalyst trained this way was bound to have the wrong idea about psychic suffering: that it was an illness to be isolated and cured by the doctor. This was a form of piety that Freud could not tolerate. “As long as I live,” he wrote, “I shall balk at having psychoanalysis swallowed by medicine.”

It is self-evident to any doctor who has treated patients with mental illness or chronic pain, or almost any kinds of functional disorders, that the patients suffer at least as much from over-zealous prescribing and medical meddling as they do from whatever it was that they first presented with. Our medical interventions are not just futile, but harmful. They’re dangerous, addictive, and trap patients in dependency After a while their symptoms have as much or more to do with the treatments they’ve been given as with the problems they started with.

Paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnacott, reflecting on his career wrote,

“It appals me to think how much deep change I have prevented or delayed in patients in a certain classification category by my personal need to interpret. If only we can wait, the patient arrives at understanding creatively and with immense joy, and now i enjoy this joy more than I used to enjoy the sense of having been clever. I think I interpret mainly to let the patient know the limits of my understanding. The principle is that it is the patient and only the patent who has the answers. We may or may not enable him or her to encompass what is known or become aware of it with acceptance.”

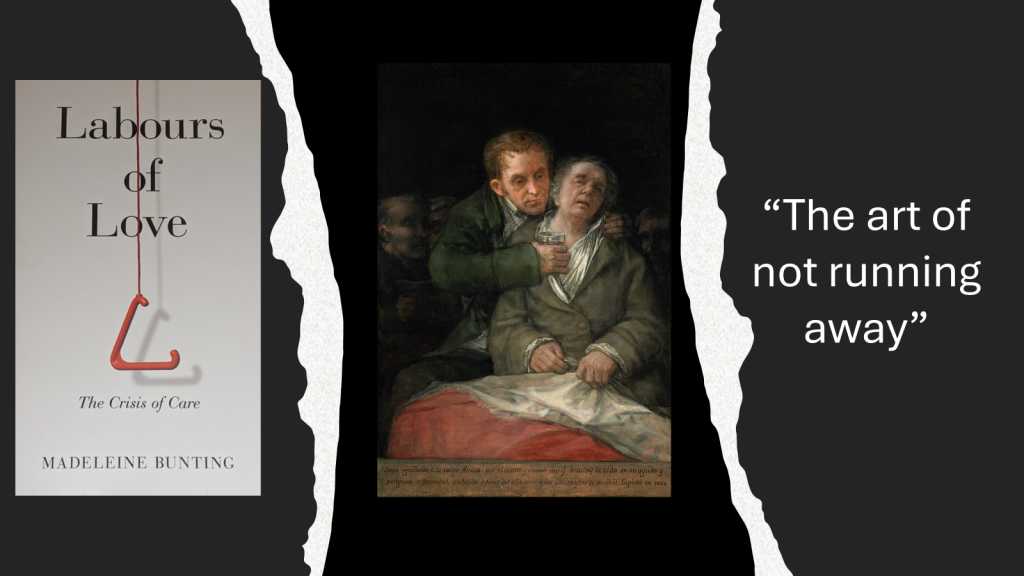

Notwithstanding the fact that patients also experience therapy as futile and sometimes even harmful, a better appreciation and understanding of existential suffering among medical practitioners is surely needed. Palliative care clinicians may understand this best of all, but they are exceptional in not being caught in the bind that ties the rest of us which is the need for restitution. Patients don’t come to doctors for therapy; they come for a diagnosis and a cure. Karl Max summed up Winnacot’s dilemma, and that of doctors and analysts who want to fix their patients when he wrote,

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the task however is to change it”

GPs may well object that they barely have sufficient time to address the medical causes of suffering, never mind the all too conscious suffering due to precarity, violence, and politics to be probing their patients’ unconscious. I would argue that existential dimensions cannot be managed separately because they are integral to what makes suffering so hard to bear.

Some patients too will resist, after all they have come for a medical diagnosis. John Berger wrote in A Fortunate Man about the importance of a medical diagnosis. Illness creates a sense of unease, a sense that something is happening to the patient and threatening to become part of the patient. When that thing is given a name and diagnosed by a doctor, it can be held at bay and treated as an entity apart, extrinsic to the patient’s self. The advent of online consultations means that every patient completes a short section to say what they think is wrong and what they think they need. It’s striking how many want all their hormones, vitamins and minerals tested, and how many want to be tested for ADHD and Autism. They hope that the cause of their symptoms can be explained in ways that can relieve them of the burden of having to change themselves or learn to live better with suffering.

Illness diagnosed is something that can be treated; existential suffering must be endured. As Buddhists know, life is suffering, and we must learn to suffer better. For Freud the aim of therapy was to help patients move from pathological misery to ordinary unhappiness.

The answer then, cannot be a dichotomy between analyse or cure, but what many most patients need is a doctor who can do both. And as with Winnacott’s concept of ‘the good enough mother’ doctors need only to be good enough therapists, which is still a heady aspiration. We can begin by prioritising continuity of care so that relationships and trust between doctors and patients can develop over time. We need to broaden training to include psychoanalytic and psychological insights. Bad therapy can be harmful, but in my experience it’s considerably less harmful than unnecessary medical drugs and procedures. Patients need someone who can make a diagnosis that accounts for suffering that can be treated medically, and existential suffering that is not an illness that can be isolated and cured. Anatole Broyard wanted a doctor that could feel his prostate and his soul, and I think that is what most patients need.

Further reading:

Sigmund Freud: Civilization and its Discontents

Ami Srinivasan: The Impossible Patient, London Review of Books, Dec. 2025

Mark Solms: The Only Cure – review https://www.theguardian.com/books/2026/jan/12/the-only-cure-by-mark-solms-review-a-bold-attempt-to-rehabilitate-freud

Longing for ground in a ground(less) world: a qualitative inquiry of existential suffering

Suffering a Healthy Life—On the Existential Dimension of Health

Anatole Broyard: Intoxicated by my Illness

- Primary prevention should be the duty of every political department apart from Health and Social Care. It is about preventing illness and suffering due to the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age. These are the social determinants of health. Secondary prevention is the early detection of disease through screening. Tertiary prevention is the main work of the NHS – taking care of people who are sick and/or have long-term conditions, to reduce suffering and avoid or minimise complications. Quaternary prevention is the avoidance of harm due to medical interventions including medical errors and excessive interventions.