Confidence and trust in GPs.

This weekend I went to a ‘nine-night’, a memorial for a Caribbean patient I had known for almost 20 years. I remember vividly the first time we met. She walked into my consulting room and stood right in front of me just as I sat down. Almost six-foot tall and considerably more than a hundred kilos, she leaned over me and banged her walking stick wrapped in silver lamé on the floor, “I don’t know you and I don’t like doctors, especially doctors I don’t know. What you need to know is that I need a doctor who can be comfortable in front of me,” I looked up to see her frowning down at me and I was about to say, “I think I can do that,” when she cracked into a grin and slapped me hard on my shoulder and said, “I’m only kidding! Dr Fuller said I should see you and I trust him! But he’s left. You had better not leave, because if you’re not staying, I’m going somewhere else.” She wasn’t kidding, especially about needing a doctor that could remain comfortable in her considerable presence. Philosopher Julia Kristeva wrote ‘Powers of Horror: an essay on abjection’ in which she described abjection as having both visceral and symbolic powers. Visceral powers relate to its ability to disgust and repel, forcing people in its presence to recoil, repel or escape. The symbolic powers relate to the ways that abjection transgresses boundaries between life and death, clean and contaminated, what is permitted and what is not. Janet crossed a boundary by ignoring the patient seat in my room and leaning over me. Her body made huge by binge eating and scarred by surgical procedures and self-harm was a battleground where she was both victim and perpetrator, abject even to her. She had met too many doctors who recoiled in her presence, but having been assured by her previous GP that I would be up to the task she wasted no time before testing me. Looking back through her medical record I can see that it wasn’t long after our first meeting that she told me about some of the abject horror of her childhood that helped make sense of her present situation. In recent years when she was housebound she would insist on cooking for me when ever I came to visit. if she was unwell she might postpone the visit for a day or two until she had mustered the strength to prepare something. She bought a portable hob and electric wok so that she could sit on the side of her bed in the lounge and cook up Caribbean fusion dishes with meat, fish, chicken, rice, past and vegetables and always with hot pepper sauce on the side. She was impressed and amused by how much I enjoyed the spices. I would always be sure to skip breakfast and do a training session before work on days when I was due to visit because she would be disappointed if I didn’t eat A LOT. While I was eating, I couldn’t interrupt her and she had my full attention. My mouth was full and my ears were open. We would catch up on her hospital visits and her precarious health, and she would cry and try desperately to get me to understand how she felt, especially after her son died. Empathy came more from shared feeling than from words. I never saw her eat anything herself. After she died I looked through the dozens of consultations that I had recorded and wondered how many people knew as much as I did about her life.

“When you [a GP] are so poor that you cannot afford to refuse eighteenpence from a man who is too poor to pay you any more, it is useless to tell him that what he or his sick child needs is not medicine, but more leisure, better clothes, better food, and a better drained and ventilated house. It is kinder to give him a bottle of something almost as cheap as water, and tell him to come again with another eighteenpence if it does not cure him. When you have done that over and over again every day for a week, how much scientific conscience have you left? If you are weak-minded enough to cling desperately to your eighteenpence as denoting a certain social superiority to the sixpenny doctor, you will be miserably poor all your life; whilst the sixpenny doctor, with his low prices and quick turnover of patients, visibly makes much more than you do and kills no more people.

A doctor’s character can no more stand out against such conditions than the lungs of his patients can stand out against bad ventilation. The only way in which he can preserve his self-respect is by forgetting all he ever learnt of science, and clinging to such help as he can give without cost merely by being less ignorant and more accustomed to sick-beds than his patients. Finally, he acquires a certain skill at nursing cases under poverty-stricken domestic conditions.”

George Bernard Shaw, The Doctor’s Dilemma 1909

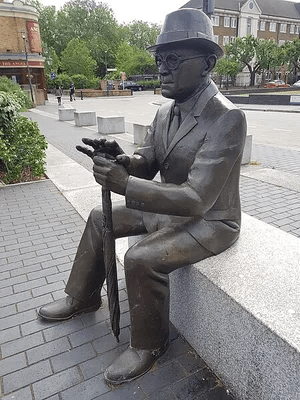

Dr Alfred Slater was a GP who worked in Bermondsey at that time and may have been an inspiration. He charged six pence for consultations if patients could afford it and nothing if they could not and in spite of this he was soon able to recruit four more doctors to the practice. He worked with his wife Ada all their lives to try to alleviate the effects of poverty in the area. He upset other doctors because of his low fees, and his popularity with patients. Unlike easily manipulated and faked Google reviews that are a proxy for GP popularity today, Dr Slater earned his status by the quality of his care, his political advocacy, and his physical presence. Unlike GPs today who rarely or never visit patients at home and consult remotely, he chose to live in the heart of the community where he practiced and was, and still is, held in high esteem by the community.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/dr-salters-daydream

I have worked for twenty-five years in a practice that actively supports continuity of care and doctors and nurses do home visits every week. Even as we have expanded from four to ten GPs and from seven thousand to seventeen thousand patients, we have kept the same philosophy of relationship centred care. Our social standing and the confidence and trust on which we and our patients depend, is sustained by this.

This is not just a philosophical or moral issue, but there is an abundance of research supporting my view that the more distant GPs are from their patients, the lower the confidence and trust patients will have in us. Our ability to contain anxiety, manage uncertainty, diagnose promptly, and take care of patients depends on the strength of our relationships with patients and the community.

The Royal College of GPs curriculum for GP training states that ‘Continuity of care, along with generalism is a fundamental feature of general practice,’ and yet continuity is vanishing and patients are increasingly viewing GPs as gatekeepers, shopkeepers, dealers and travel agents. And a lot of GPs are quietly slipping into these roles, some passively and some actively. The emphasis on work-life balance has come about because meaning and purpose is intrinsic to a working practice bound up in relationships with patients and community, but is entirely lacking from the transactional model which alienates GPs from their patients, their work and themselves.

Just have my patients have taught me the value of continuity of care, my trainees have shown me that if they are given the chance to experience some of the satisfaction and pride that comes from investing in relationships with patients they will want more of it. This way we can build a better future for general practice. Where there is a will there is a way. I want to be proved wrong, and the 2025 GP patient survey suggests that I may be, But I think that the truth is that the status of our profession like Wile E. Coyte who has run off the edge of a cliff but doesn’t realise it and hangs briefly in the air before plummeting down to the canyon before. We only have ourselves to blame.

References:

List of Critically Endangered Crafts in which General Practice will soon be included: https://www.heritagecrafts.org.uk/skills/crafts/

The Doctor’s Dilemma, Preface on Doctors by George Bernard Shaw https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5069/5069-h/5069-h.htm#link2H_4_0008

Dr Alfred Slater, the man who created an NHS before the NHS was created https://stephenliddell.co.uk/2017/11/30/dr-alfred-salter-the-man-who-created-an-nhs-before-the-nhs-was-created/

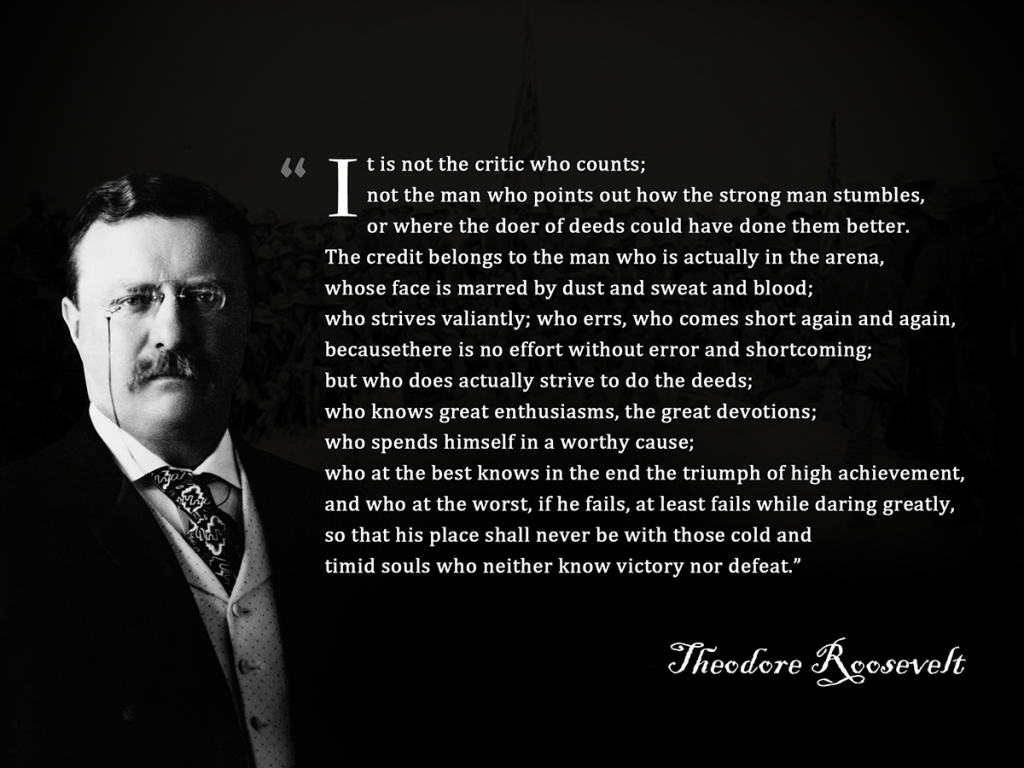

Man in the Arena speech by Theodore Roosevelt https://www.worldfuturefund.org/Documents/maninarena.htm

Alienation and the Crisis of NHS Morale https://abetternhs.net/2023/08/28/alienation-and-the-crisis-of-nhs-staff-morale/

Factors influencing confidence and trust in health professionals: A cross-sectional study of English general practices https://bjgp.org/content/early/2025/10/03/BJGP.2025.0154

The GP Patient Survey 2025 https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/the-results-are-in-gps-do-an-amazing-job