Originally published in BHMA https://bhma.org/product/facing-the-shadow/

At his interview for a position at a law firm, a friend was asked what he would arrange for the partners’ away day. With barely a pause he said that he would take them to a mortuary, and they would look at dead bodies and afterwards they would gather to reflect on their confrontation with death. He persuaded them that our morality is constrained because we are too removed from death, and too fearful of our own mortality. He got the job, but never actually took them to the mortuary.

A few years later I happened to pass by St Pancras Public mortuary with my teenage sons and was reminded of my friend and suggested that we go inside. They recoiled at the idea and vehemently refused. The strength of their response surprised me, their disgust and their refusal. Teenagers are exposed to more horror than most parents can imagine. My sons tell me of a day this February when all the usual social media filters failed and their Instagram and Tiktck feeds were full of graphic videos of acts of extreme violence, far worse than the usual day to day horror that intrudes on their music, fashion and skate-boarding feeds. Younger children dare each-other to watch videos of extreme violence, but by the time they are twelve or thirteen (my sons tell me) some lose interest, and choose to avoid it, partly because of the human suffering, but also part because it’s intrusive and tedious.

Horror is tolerable when it is in its place and accompanied by rituals – in the mortuary, the dissecting room, the operating theatre, on the battlefield, in hospitals and nursing homes, in art, in religion, in therapy and in the consulting room. Even in the right places with the right rituals, there are limits to how much horror can be tolerated. Few people who are unmoved by dead bodies on the news or in movies would want to see a body in a mortuary or at the scene of an accident. Some doctors cannot stomach the sight of blood and choose specialties where tears are the bodily fluid more frequently encountered. Other doctors choose to practice in affluent areas or to do private medicine where they do not have to encounter the scents of poverty, so vividly described by Dr Jens Foell,

What exactly is this smell of poverty? It is so pervasive. I recognise it in an instant. This perfume should be called ‘Deep End’, and it gives every encounter with poverty a visceral olfactory dimension. It is described as the ‘smell of rotten fruit’ in the beginning of the Akira Kurosawa’s film, Red Beard, which features Toshirô Mifune as a doctor treating the poor.[i]

My recent round of home visits for long-term housebound patients included a psychotic woman who keeps dozens of birds in her flat that fly around everywhere. Every surface is covered in faeces and the whole has an overwhelming scent that is partly ammonia but otherwise wholly unfamiliar. Another patient stacks towels soaked in urine on the arm of her chair until the carers come in the evening, and the air in her flat is suffocating. Neiter patient ever opens their windows. My stomach tightens whenever I am asked to visit. I am glad that I have a shower and change of clothes at work.

Philosopher Julia Kristeva wrote about confrontations like this in Powers of Horror: an essay on abjection. The abject has symbolic and somatic effects. The somatic is sensory, anything that evokes disgust like foul smells, death, decay, infected wounds, skin diseases and infections, bodily fluids – mucous, pus and faeces. These provoke physiological sympathetic nervous system reflexes like nausea, sweating, palpitations, feeling faint, and desire to escape (flight), or defend oneself (fight), to recoil, to avoid and end the experience as soon as possible. Horror’s symbolic power comes from boundaries being broken, the symbolic order disrupted. Being too close to death, we are confronted with our own mortality, too close to madness we are confronted with the limits of our own sanity. When boundaries are intact, we can cope because there are clear lines separating us from what we are not. Philosopher and novelist John Berger wrote,

“The poor live with wind, with dampness, flying dust, silence, unbearable noise (sometimes with both, yes, that’s possible), with ants, with large animals, with smells coming from the earth, rats, smoke, rain, vibrations from elsewhere, rumours, nightfall, and with each other. Between the inhabitants and these presences there are no clear marking lines. Inexorably confounded, they together make up the place’s life.” John Berger, Hold Everything Dear 2007

Confronted with abject patients, doctors may may to defend themselves by saying that it’s not their job, that they don’t have enough time, that they aren’t trained or suitably qualified, that these kinds of abject patients and these kinds of abject problems do not belong with them.

“The rich force the poor into abjectness and then complain that they are abject” Percy Shelly 1812

Doctors choose their profession because they believe that they can make a difference. For a trauma surgeon, confrontation with appalling injuries is made tolerable by their ability to act, to repair the damage. The symbolic order is preserved because they are performing their role and the patient as victim is performing theirs. The symbolic order is upset when the doctor is unable to perform in their accustomed role, and their identity is threatened.

A group of medical students were sent to visit a patient at home. Compared to many, his situation was not so abject, but a mix of animals, incontinence and smoking generated a familiar ‘Deep End’ scent that clung to their clothes. The students were unhappy, they protested that it was unreasonable and inappropriate, and they did not want to do any more visits. Their tutor, a GP with decades of ‘Deep End’ experience was shocked, she had hoped for empathy, compassion, and curiosity. The abject crossed the boundary between the students and the patient by finding a home in their clothes and in their noses, following them around even after the visit was over. It was revolting and out of place. Unlike me, they couldn’t change their clothes, and unlike the trauma-surgeon, they were powerless to intervene in any meaningful way.

In her essay, The Art of Doing Nothing, Iona Heath explains that in medicine, “the art of doing nothing is active, considered, and deliberate. It is an antidote to the pressure to do and it takes many forms.” She quotes Arthur Kleinman, the American anthropologist and psychiatrist, who says:

… empathic witnessing … is the existential commitment to be with the sick person and to facilitate his or her building of an illness narrative that will make sense of and give value to the experience. … This I take to be the moral core of doctoring and of the experience of illness.

Many patients are exquisitely sensitive to their doctor’s actual or perceived judgement. It is very common for patients to refuse a visit or postpone an appointment so that they can clean their home or make themselves presentable so that they won’t be judged. They can see disgust in their doctor’s eyes. Whenever I ask patients questions about their lifestyle they are almost always drinking less, exercising more, eating less junk, getting out more. Far from exaggerating their symptoms, most patients hate to disappoint their doctors, and they reassure us that they are taking their tablets and that they are getting better even when they are not. As a GP with 25 years of continuity of care, I know my patients disclose the horror of their lives very slowly and frequently apologies for overburdening me. They know implicitly that there’s only so much that even a doctor can bear. This is most frequently the case when there are histories of abuse. Shame is intensified if the doctor recoils, refuses to listen and pushes them away into the purgatory of a waiting list for psychotherapy.

Abjection collapses the distinction between subject and object and leads to an intersubjectivity rooted in extremes of difference: life vs death, comfort vs squalor, privilege vs powerlessness, safe vs violated, flourishing vs decaying etc. Work with the abject is emotional labour because the intersubjectivity means that like the smells that linger, experiences linger after the work is done. It is easy to criticise the hours worked by junior doctors in the time before I qualified, but the benefits of camaraderie and down time in the doctors’ mess where experiences could be processed with peers have been all but forgotten [ii]. Soldiers returning from active service need the company of others who can relate to their experiences to help them transition back into family life just as survivors of natural and man-made disasters need the company of other survivors. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is much more likely without this among fellow survivors. In the years since I qualified, almost all doctors have become more isolated and are seeking greater work-life balance, in other words, clearer boundaries. Without appreciating that any meaningful work worth doing is part of life, and that personal healing has to happen as part of work. We need liminal zones between work and leisure to process and reflect on our experiences.

Doctors and other health professionals deal with the abject and as educators we can help them prepare for this, but few have even considered what it means or how to do this. Fortunately, since the abject is part of what it is to be human, we have evolved ways to cope. Kristeva believed we have always used art and religion, and I believe that that the more familiar doctors are with each of these, the better they can cope with the abject in their work. The Eisenheim Altarpiece from 1512 depicts Christ covered with open sores. It was painted for a monastery where monks cared for people afflicted by the plague and other awful skin diseases [iii] The symbolic power of Christ covered in sores, would have helped them see the body of Christ in those the cared for.

For Kristeva and GP Iona Heath, literature is the place where the abject is best explored and Iona’s writing tackles the places where meaning in medical practice and is examined with a rich tapestry of literary references. [iv] Her William Pickles Lecture from 1999 uses the poems of Zbigniew Herbert and Michael Frayn’s play ‘Copenhagen’ to explore uncertainty and hope,

Herbert requires us not to delude ourselves about the nature of the reality we inhabit and witness. Seamus Heaney describes Herbert’s: unblindable stare at the facts of pain, the recurrence of injustice and catastrophe.

She goes on to emphasize the need to invite intersubjectivity and frequent theme in her writing,

Without the ability to oscillate between the subjective and the objective, medicine is powerless: The first diagnostic step rests on intersubjectivity, and the second on a striving for objectivity.

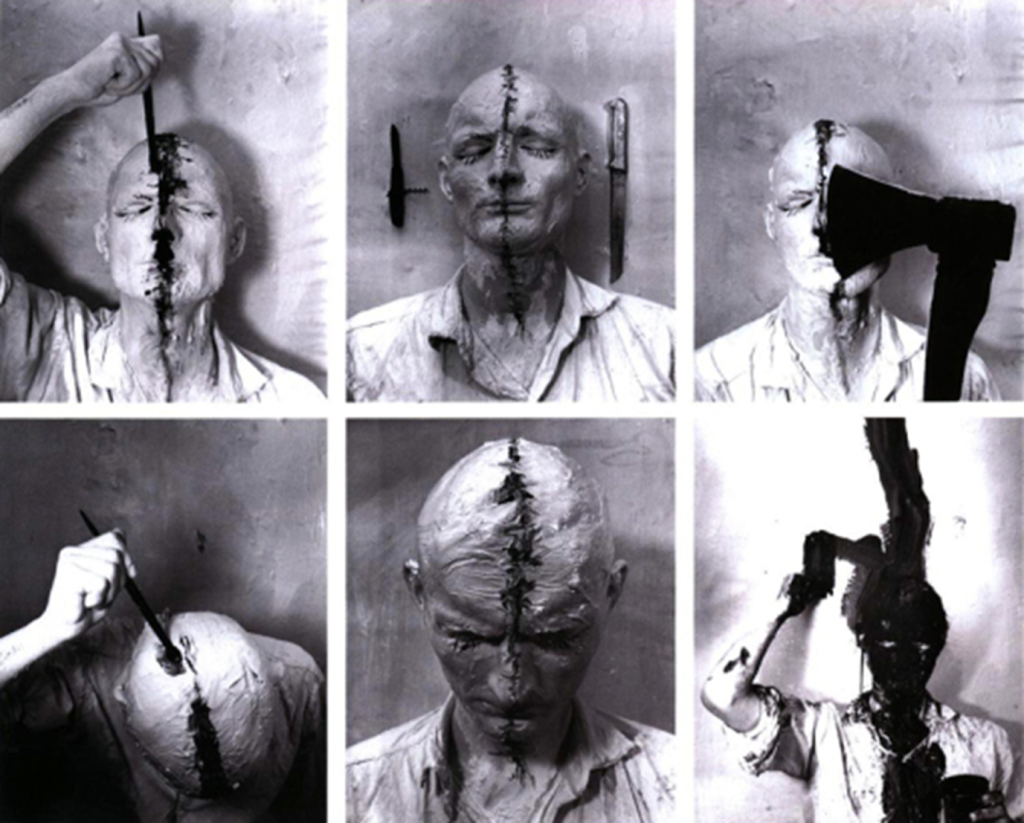

Recent popular novels like A Little Life, Shuggie Bain, and Demon Copperhead have given medical readers a safe space for intersubjectivity, and with it, ways to think about and be more curious about the abject lives of their patients. Most patients, especially those dealing with abjection – pain, despair, death, shame, incontinence, and so on, don’t just (or even) want scientific explanations for their symptoms but for their doctors to have a better understanding and appreciation of what life is like for them. In Regarding the Pain of Others, philosopher Susan Sontag examined our relationship with images of suffering and was concerned by the ways in which ever more shocking photographs were used to attract attention and drive consumption without demanding understanding or action. Extreme abjection in art has been used to provoke and draw attention to political and historic horror that people have been unable or unwilling to deal with like complicity with Nazism. The Vienna Actionists – a group of artists active in the1960s gave obscene and shocking performances involving bodily fluids and violent sexual acts transgressing physical boundaries between artists and audiences including unsuspecting passers-by [v].

Abjection breaks moral and sometimes legal boundaries which has led to the artists being arrested [vi] American Artist Paul McCarthy working from the 1970s onwards used liquid food stuffs in lieu of bodily fluids in several works including Class Fool 1976 in which he covered himself in ketchup and thew himself around a classroom until dazed and then vomited several times and stuck a Barbie Doll up his arse [vii]. The show ended when the audience couldn’t stand it any longer. Although he distanced himself from the Vienna Actionists on the grounds that he didn’t share their cultural history, like them he wanted to confront audiences with their hypocrisy and complicity in mindless consumerism, violence and oppression. Movie directors have also used the abject to confront similar themes. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s1975 film Salo: 120 days of Sodom remains banned in several countries and was described by Time Out Magazine as the most controversial film of all time [viii]. He used themes of extreme sexual violence, coprophagia and torture to attack fascism and consumerism.

Zombie movies are a favourite trope for criticising consumerism and consumer culture, from George Romero’s 1868 classic Night of the Living Dead, to Peter Jackson’s 1996 Brainsead [ix]. Brain Dead remains banned in several countries and has a scene that echoes Kristeva’s idea that an infant develops a sense of self as separate from their mother at the point in their development when they experience abjection. Infants are not born with a sense of the abject; they are content to play with shit and are unperturbed by vomit. Near the end of Braindead a sixty-foot zombie woman shoves her adult son back into her womb shouting, “You will always be my little boy!” He then cuts himself out of her stomach and she collapses into a burning house. Zombies are a classic abject trope because their power lies in our not knowing whether they are alive or dead, our fear is the undead, the unknown, it is apprehension and uncertainty, themes that presently preoccupy medical educationalists, few (or even none) of whom refer to abjection.

An inability to tolerate uncertainty, especially moral uncertainty or ambiguity is associated with more conservative and extreme political views [x]. Clearly defined boundaries between right and wrong, good and bad, acceptable and unacceptable, are hallmarks of political intolerance, populism and nationalism, in short, fascism, which is why so much abject art and cinema are anti-fascist. My colleague’s medical students who were disgusted by what they encountered on their home visit were unable to see beyond the state of the patient and their home to the political and economic decisions that led to such an abject situation. For Susan Sontag, abject encounters have an ethical value, “Such images … [are] an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by established powers. Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible?” [xi] As Sontag noted, they are an invitation that may be ignored, rejected, or not noticed. In the fruit-machine meets TV world of social media, a surfeit of abject images streams past demanding consumption without reflection.

Artist Jenny Saville’s pictures, “..may be painful to see, while the painting of it, if not quite pleasurable to see, is so extremely compelling of our attention that we do not want to look away…” She wrote her final college dissertation on Kristeva and her influence shows in works across her career which began with her final show in 1992. Her most famous piece from that show, Propped is a huge self-portrait of a huge woman, sat naked on a stool, with her ankles and arms crossed and her fingers digging into her soft, fleshy thighs. The viewer’s perspective is from the level of her enormous knees, so that they must look up at her while she peers down at them over her nose with her head tilted back. She dominates the viewer.

Etched into the painting are words by feminist author Luce Irirgaray, which translated reads, “If we speak to each other as men have been doing for centuries, as we have been taught to speak, we will fail each other. Again… Words will pass through our bodies, above our heads, disappear, make us disappear”. Saville paints women in ways men do not.

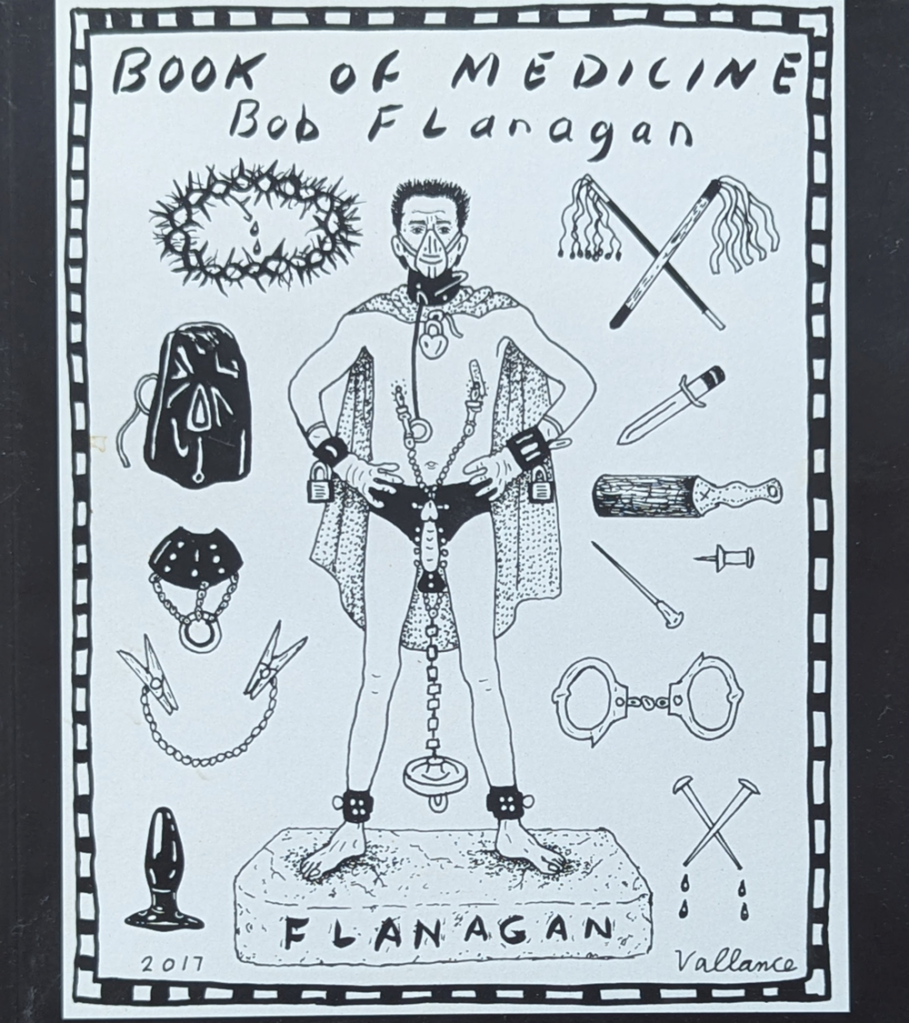

In later works she fills enormous canvases with flesh that cannot be contained by bodies but blends in with everything and everyone around it. The abject is matter out of place, and she paints the flesh of mothers mixed with their babies, lovers blended with one another and groups who seem to share limbs and torsos. Recent portraits are like mirages that appear out of big, bright abstract brush strokes, splashes, and lumps of paint. Artists who work with abject ideas are concerned with the many ways of being in the world and show us what is socially or psychologically taboo. Bob Flannagan was another artist who used himself as his abject art. He suffered with Cystic Fibrosis, a condition that caused his lungs to fill with pus, leading to frequent infections and hospitalizations, he had diarrhoea and frequent, foul, mucousy stools, chronic pain and depended on medication, nutritional supplements, oxygen therapy and physiotherapy. His art centred on his body, his disease and masochistic body mutilations, presented as visual art, performance poetry and physical theatre. The chosen pain of masochism and masochistic sex overwhelmed the pain he was forced to endure because of his illness.

Physical presence demands more and is one reason why in-person medical care is challenging to medical professionals who are retreating to do only virtual consulting. They are spared multisensory experiences and can escape a consultation that makes them feel uncomfortable almost as easily as they can swipe away an unpleasant image on their phone. For those of us who remain in consulting rooms and communities, home visits are where we have the most immersive experiences.

Clive speaks eloquently with a clipped English accent and assures me everything is fine at home which seems out of place given the sweet, soured milk smell that seeps out of several layers of dirty clothes. He has dreadlocks piled up and matted on his head and a huge woollen jumper in Jamaican colours unravelling in several places. A fistful of cuffs at wrists and ankles suggests that examining him might require a lot of undressing. His smell is so pungent that I am hoping that might not be necessary. Without this assault on my senses, I would not have sensed that behind his reassuring words, all was not ok. I asked whether he had hot water to bathe or shower at home, and he looked embarrassed and fiddled with loose threads. He finally admitted that his water and electricity had been cut off a couple years ago and he was going to a homeless centre every couple of weeks to wash and was a bit overdue. I examined him, conscious of the time in my youth when Princess Diana shook hands with people who were dying from AIDS while the nation looked on, astonished at her bravery and compassion, and I eschewed gloves. His smell lingered heavily in my room and my clothes, or at least my consciousness, for the rest of the day.

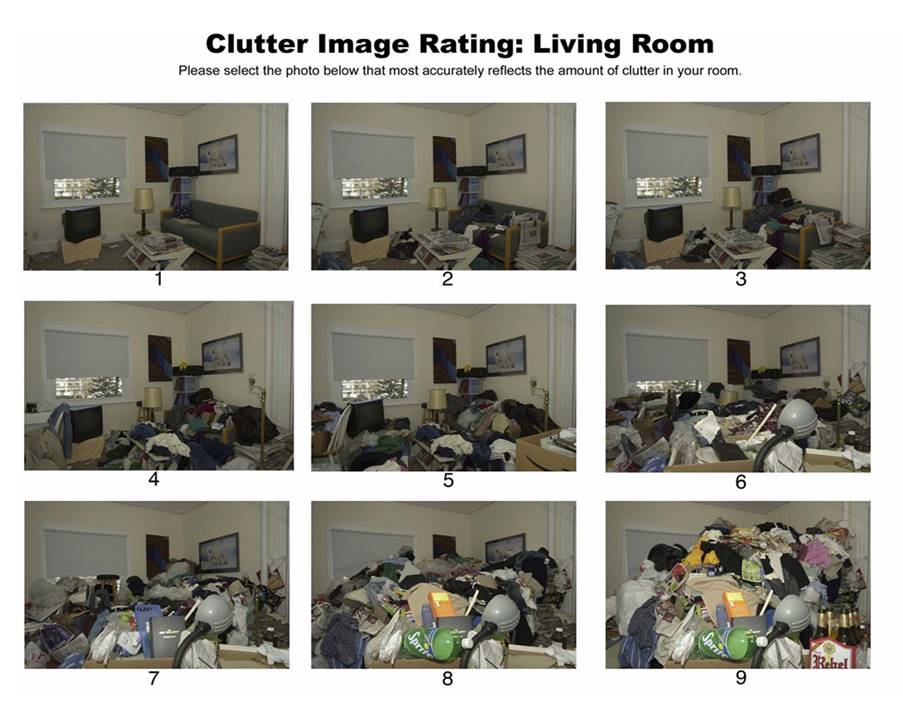

A few days later I visited him at home, he was a hoarder, level 9 on the Cluster Image Rating (2008) “This level of hoarding constitutes a Safeguarding alert due to the significant risk to health of the householders, surrounding properties and residents.” [xii] Boxes, bags and miscellaneous detritus were piled from floor to ceiling, with only narrow paths allowing access to his bed and a single seat in the living room. Without water or electricity, the bathroom and kitchen were redundant, and access was impossible. I wondered whether I would ever have known about his situation were it not for our first, face-to-face, multi-sensory encounter.[xiii]

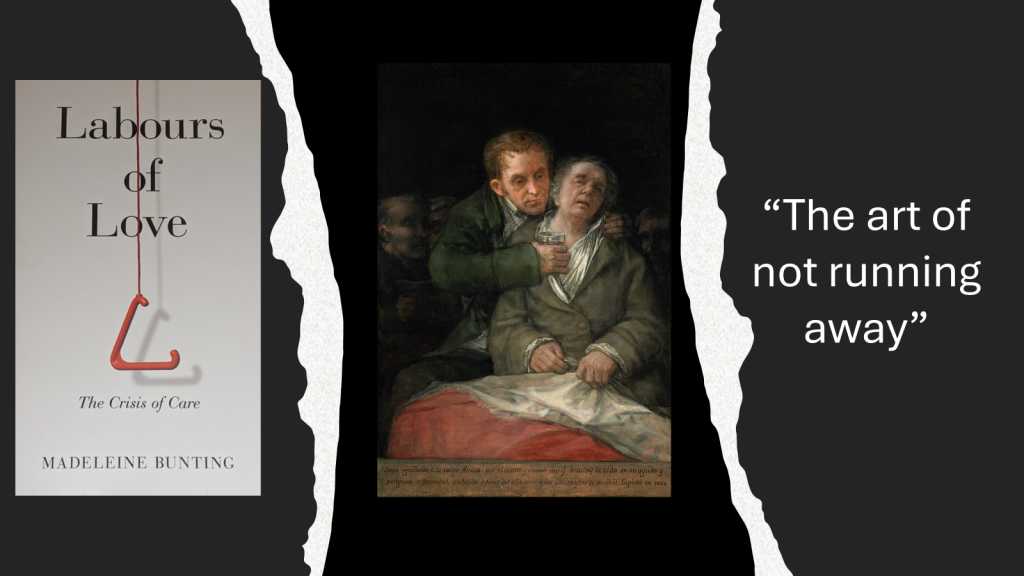

The classic Kurosawa movie Redbeard is about a GP trainer and his trainee, set in 19th century Japan. When the outgoing trainee hands over to his replacement Yasumoto, he warns him, “the patients are slum-dwellers, flea and lice-ridden, they stink!” Yasumoto aspires to be physician to the Shogun, not a GP to impoverished villagers and is disgusted and reluctant to have anything to do with them. Abjection confronts the young doctor, and the movie has several abject themes including squalor, child abuse and suicide. Redbeard teaches by example and by giving Yasumoto responsibility for taking care of a girl he rescued from a brothel. Care-giving is the most profound and intimate way in which we can encounter the abject. In her review of Kindness in Healthcare, Iona Heath writes, “it is easy to forget the appalling nature of some of the jobs carried out by NHS staff day in, day out—the damage, the pain, the mess they encounter, the sheer stench of diseased human flesh and its waste products.”In Labours of Love, by Madeline Bunting, a book about the nature and crisis of caring she quotes a palliative care consultant who describes caring as, ‘the art of not running away, also the title of an essay I have written about care-giving’[xiv].

A better appreciation of abjection teaches us to be present with what instinctively repels us, whether by assaulting our senses or shocking us with narratives of trauma. Patients need doctors (and other healthcare professionals) who can remain present when the instinctive urge is to run away. We must learn how to suffer, and in so doing learn how to become more compassionate, because compassion means being with suffering and being moved to do something about it. Being fully present may be the most therapeutic gift a practitioner can offer and caring in situations of abjection may be the best way that we can do that[xv] [xvi]

This is the first in a series of essays about art, abjection, self-representation and medicine. Please contact me, Jonathon Tomlinson echothx at gmail dot com. I am available for teaching sessions and workshops for health and social care professionals and anyone working at the interfaces of medicine, culture and society. I work with FlyingChild to do side-by-side professional and survivor education for health professionals.

[i] https://bjgp.org/content/75/753/174.full

[ii] https://abetternhs.net/2013/11/23/burden/

[iii] Isenheim Altarpiece – Wikipedia

[iv] https://abetternhs.net/2012/09/19/iona-heath/

[v] https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/viennese-actionism/

[vi] https://momus.ca/abjection-without-splendor-gunter-brus-and-transgressions-diminishing-returns/

[vii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_McCarthy

[viii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sal%C3%B2,_or_the_120_Days_of_Sodom

[ix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Braindead_(film)

[x] Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D., Iyer, R., & Haidt, J. (2011). Disgust Sensitivity, Political Conservatism, and Voting. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(5), 537-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611429024 (Original work published 2012)

[xi] Sontag, Susan: Regarding the Pain of Others 2004 Penguin

[xii] Day, John. Hordiculture. London Review of Books Vol. 44 No. 17 · 8 September 2022

[xiii] Clutter Image Ratings – Hoarding Disorders UK

[xiv] https://abetternhs.net/2020/11/15/the-art-of-not-running-away/