One of the most haunting images from my time as a junior doctor working in Hackney in the mid-1990s was in an A&E (emergency) department while we tried to resuscitate a man in his 40s. In the corner of the room stood two young children – probably about the same age mine are now, 6-8 years old. They stood and stared in silence, watching us trying to save their dad. He was covered in blood and bile, his body yellow with jaundice, veins visible on his abdomen and torso from advanced, alcoholic liver disease. His wife was in another part of the department, so intoxicated she couldn’t stand, barely conscious and unaware of what was happening to her husband and children. The children were eerily impassive. The ambulance crew told us that when they arrived at their flat, they were trying to wake their dad while their mum lay unconscious, snoring in the next room. The flat was squalid and the children were obviously severely neglected. By now they will be in their mid to late 20s, assuming they are still alive, possibly with kids of their own. I wonder what became of them.

A lot of my time in A&E in south east London was spent with young people, mostly women and girls who cut themselves or took overdoses. I absorbed the culture of my workplace – where they were usually treated as ‘timewasters’ and where ‘PD’ which stands for ‘Personality Disorder’ was a term of abuse. I quickly became aware that all of them had been abused (usually sexually) or neglected severely, but I struggled to find anyone who knew what we could do to help, and faced with our own helplessness we continued to patch them up, push them away, and complain about them wasting our time. I remember one night meeting a teenage girl who wanted treatment for sexually transmitted infections, she refused to be examined, protesting that it was too sore, too smelly and too embarrassing. She looked terrified. I was the only doctor in a busy department in the middle of the night – she slipped away before I had an opportunity to find out any more.

I rotated between junior doctor posts, driven by a mixture of curiosity and an inability to commit to a specialty at an early age. After A&E I worked as a junior surgeon and gynaecologist where I met dozens of patients (also mostly young women) whose enormous hospital records documented their repeated admissions, investigations and surgical procedures. We couldn’t explain their abdominal pain and bloating, pelvic pain and unexplained severe constipation or incontinence. Some of them also cut themselves, but mostly we examined the scars that criss-crossed their abdomens made by surgeons, looking for the source of their symptoms in the organs underneath.

I spent just 3 months working part-time in sexual health, barely long-enough to wonder why just a few young people (again, mostly women) accounted for such a high proportion of the visits.

As a young, naive paediatrician I saw kids with ADHD and other conduct disorders, many of whom had a dysfunctional home environment. Some were adopted, but we were strangely uncurious about what had happened to them before they were adopted. I met countless parents who were overwhelmingly anxious, who bought their children to hospital week in, week out. Some seemed to spend every Friday night in A&E. I focussed on the children and it hardly ever crossed my mind to think about what had happened in their own lives, or might still be happening, that rendered them so fearful.

I spent 6 months as a junior psychiatrist where I had a little more time to listen to patients, but many refused to talk for long to a doctor they had never met before and might never meet again. I struggled to find ways to find the information that mattered most to the patients I read their extensive discharge summaries but struggled to find out which events were the most significant in their lives. It was clear that mental ill health had a complex aetiology – which is to say that similar illness were clustered in families, were affected by experiences, and were worsened by deprivation, intoxication and isolation, most of which we had no ability to influence. For some people psychosis struck someone in the most stable of social circumstances, but for most it was chaos superimposed on chaos. We prescribed every new drug that came on the market, usually on the basis of the earliest trials and negligible evidence of benefit. The side effects – “They’ll make you fat and impotent!” one patient yelled across the ward as I tried to persuade another to try them, were more predictable than the benefits.

As time went on I realised that if I wanted to understand why people suffered from unexplained symptoms, chronic pain, anxiety, depression and psychosis I would need work somewhere where continuity of care was valued and protected.

For most of the last 17 years, I’ve been a GP working in Hackney in East London. We serve an increasingly economically diverse, but still very deprived, young, socio-culturally mixed group of patients.

A lot of what many people would consider to be ‘normal general practice’ – managing diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, minor illnesses and so on, is managed by practice nurses, specialist nurses, clinical pharmacists, GP trainees and salaried doctors. GPs like myself who have been around for long enough to develop therapeutic relationships with patients spend most of our time with patients who suffer from chronic pain, medically unexplained symptoms, addiction, eating disorders, severe obesity, self-harm, suicidal thoughts and mental health disorders; especially chronic anxiety, chronic depression, OCD, bipolar and personality disorders. Among them are our patients with the worst diabetic complications, the most symptomatic heart-failure, the most brittle asthma and out of control hypertension. They are the same patients who I met again and again as a junior doctor, who bewildered and frustrated me and my colleagues. They are still the patients who attend A&E most frequently and are most likely to fail to attend routine reviews. If they are not asking me to give them something for their chronic pain, debilitating anxiety and insomnia, for weight loss or breathlessness they need me to write reports for housing or benefits assessments. I, and thousands of doctors like me, spend every day caring for patients like this. One thing I have only very recently learned, is that Trauma is embodied.

What is extraordinary, and to be frank, a betrayal of patients and clinicians on the part of those responsible for medical education is that we never talked about, much less seriously taught about the lasting effects of trauma. We were taught that diseases were due to the interaction of human biology and the environment, but human experiences were barely part of the picture.

Julian Tudor Hart worked for over 40 years in the same practice in the Welsh Valleys and saw the same community after the mining industry closed down. Not only did unhealthy lifestyles and mental illnesses proliferate, but so did domestic violence and incest. Without meaning and purpose, for some people, morality collapsed.

For John Launer, GP educator and narrative medicine pioneer, medically unexplained symptoms are better understood as ‘medically unexplored stories’. Most GPs, especially those who work in deprived areas, bare witness every day to their patients’ accounts of trauma; including physical abuse and neglect; parents who were, because of alcoholism, drug abuse or mental illness unable to care for their own children in their earliest years; stories of material and emotional deprivation, abandonment and loss, domestic violence, crime and imprisonment and with shocking frequency, child abuse. Trauma begets trauma so that people rendered vulnerable by trauma in childhood are very frequently victims of violence and abuse in later life. Survivors of trauma use drugs and alcohol to cope with the aftermath, then find themselves involved with crime which leads to imprisonment and homelessness and further cycles of alienation and despair.

People whose work does not involved repeated encounters with survivors of trauma frequently either cannot believe, or refuse to believe how common it is. For years it’s been assumed that people invented stories of trauma to excuse bad behaviour. The medical profession bears a lot of responsibility for this, largely ignoring the psychological consequences of rape until the last 30 years.

In 1896, Freud presented the detailed case histories of 18 women with ‘hysteria’ – what might these days be labelled ‘Emotionally Unstable Personality disorder’. In every case the women described childhood sexual abuse. Freud thought that he had found the ‘Caput Nili’, the source, of hysteria, and presented his findings in anticipation of fame and possibly fortune. What he failed to anticipate was that the upper echelons of Viennese society were not prepared to accept that women with hysteria could be telling the truth and in so doing, implicating their own, privileged social circles. Freud was sent away to come up with another, more acceptable theory. His insights were buried and forgotten for most of the 20th century.

Ruby is imposing. She is six-foot-tall and one hundred and thirty kilogrammes. She rarely goes out, but when she does she dresses up – lots of gold jewellery – pink Doctor Martin boots, a huge, bright, African print dress and a gold, sequined stick. “Do you know how long it took me to get to know and trust my last doctor?” she has asked me, rhetorically, several times since we first met, about 10 years ago, after her last GP of 20 years left. “You know what I’m looking for in a doctor?” she asked, “Someone who looks comfortable when I’m sat in front of them”. How many times, I wondered, have patients looked to a doctor for help and empathy and seen fearfulness, frustration, confusion or worse; moral indignation or disgust. I know it happens. Dozens of studies have shown that the attitudes of professionals towards patients who are overweight, who self-harm, and who have personality disorders are at least as prejudiced as the non-medical public. I know I’ve done it before. But I think I’m more aware of it now, and I’m much better prepared to bear witness to trauma.

Ruby was sexually abused by her grandfather from the age of 6 to 9. When she told her mother, she didn’t believe her, her grandfather continued to visit and the abuse went on. When he stopped abusing Ruby, he started abusing her younger sister. Ruby started eating to protect herself – to smother her emotions, to make herself less attractive, to make herself more imposing and better able to defend herself. She fought at school all the time and was repeatedly excluded. She was never asked about abuse, but if she was, she would almost certainly have denied it. Happy kids don’t suddenly double in size and start fighting unless something terrible has happened. So many adults I look after who can recall the day when they suddenly stopped being a ‘normal child’.

In 1987, Vincent Felitti a doctor running a weight loss programme for severely obese adults in the US mistakenly asked a woman how much she weighed, instead of how old she was, when she had her first sexual experience. “Forty pounds”, she replied. “With my father”. He went on to interview nearly 300 other women attending the clinic and discovered that most of them had been sexually abused. He presented the findings to the American Obesity Association in 1990 and the response was almost the same as Freud had nearly 100 years before:

When he finished, one of the experts stood up and blasted him. “He told me I was naïve to believe my patients, that it was commonly understood by those more familiar with such matters that these patient statements were fabrications to provide a cover explanation for failed lives!”

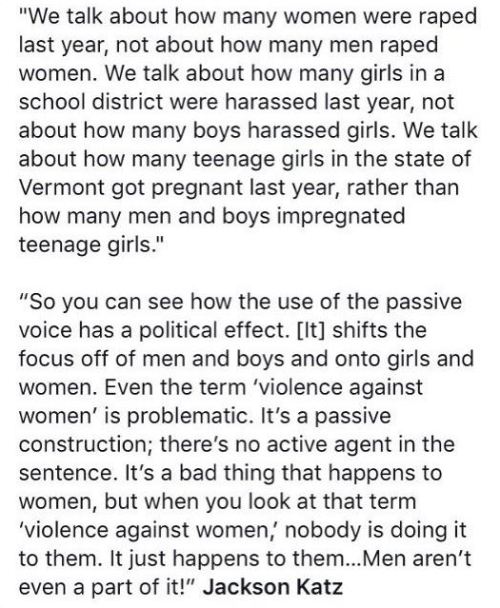

We don’t like to talk about trauma because it’s very hard to accept that something so horrific should be so common, and the perpetrators, who are usually known, so normal. Most perpetrators of sexual violence, child abuse, domestic violence and rape, have no history of trauma of their own, and no evidence of mental illness. Coming to terms with this very uncomfortable fact means accepting that there is something very, very wrong with the way we are raising young men.

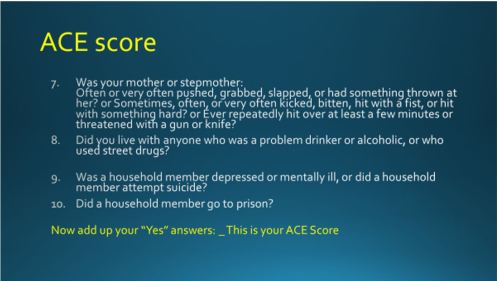

The doctors running the obesity clinic developed their line of questioning to include 10 categories of Adverse Childhood experiences listed below.

Not all categories are equally traumatising; the severity and duration of adverse experience is important in determining the extent of traumatic aftermath – the ‘trauma world’. 30-36% of people have no ACEs, but different-types of adversity go together, for example alcoholism, physical abuse and violent behaviour. The higher your ACE score the greater your risk of physical and mental ill-health and social disadvantage in the future. An ACE score of 4 or more increases the risk of heart disease 3-fold and Type 2 diabetes 4-fold. People with an ACE score of 4 or more are 6 times more likely to smoke and 14 times more likely to have experienced violence in the last 12 months. People with an ACE score of 6 or more have a life expectancy of 20 years less than those with a score of 0 because of illness, violence and suicide.

Diagnostic difficulties

Clinicians should suspect trauma in people whose symptoms and behaviour are like those I’ve described, but we need to be careful not to blame every symptom on trauma. The symptoms and behaviours associated with trauma can occur in people who have not suffered trauma. The embodiment of trauma causes lasting physical changes to the brain and body, which combined with self-destructive habits, hugely increases the risk of serious diseases. We must not forget about biology while we attend to biography. Multiple physical symptoms and associated hyper-vigilance can make it very hard for survivors and clinicians to recognise when symptoms are not a manifestation of trauma. Knowing which symptoms to investigate, and how far to go needs an experienced clinician, but often, because survivors are seen as ‘difficult’ they end up with the least experienced.

Disconnection, Fearfulness and shame: The Trauma World

While the ACE studies show that trauma is associated with a wide spectrum of illness and adversity in later life, they fall short of explaining how or why this happens. The aftermath of trauma, for those who lack the good fortune to be sufficiently resilient, is a world of disconnection, fearfulness and shame, the ‘Trauma world’.

Disconnection / dissociation.

Many people who have survived childhood abuse describe how they could separate themselves, from the act by ‘an outer body experience’ –

“He’s inside me and it hurts. It’s a huge shock on every level. And I know that it’s not right. Can’t be right. So I leave my body, floating out of it and up to the ceiling where I watch myself until it becomes too much even from there, an then I fly out of the room, straight though the closed doors and off to safety. It was an inexplicably brilliant feeling. What kid doesn’t want to be able to fly? And it felt utterly real. I was, to all intents and purposes, quite literally flying. Weightless, detached, free. It happened every time and I didn’t ever question it. I just felt grateful for the reprieve, the experience, the free high”. James Rhodes, Instrumental.

Whilst children are quite adept at this and with practice can slip into states of disconnection quite quickly, it is harder for adults. The aftermath of trauma, the trauma world, often persists or may even manifest for the first time, years after the abuse has ended. Alcohol is one of the most potent and effective dissociating drugs. Addiction specialist Hanna Pickard describes, in a radio 4 interview, the occasion when she found herself in the back of an ambulance with a broken shoulder having been knocked off her bicycle in a crash that also involved her two young children. The effect of the morphine was to profoundly dissociate her from the pain in her shoulder. She understood then how if she had also been suffering the unbearable agony of her children dying in the accident, it would dissociated her from that pain as well. Sedative drugs prescribed to treat chronic pain and chronic anxiety – opiates, anti-epileptics, antidepressants and benzopdiazepines are almost entirely unselective – they even numb the pain of trauma, hopelessness and despair.

We can disconnect from memories and aspects of ourselves that we cannot bear or are afraid to acknowledge without drugs or alcohol. For some people, excessive work or exercise can achieve similar effects, especially when it involves pain and self-sacrifice and can even drive exceptional success in academic or athletic performance. But in spite of this, because trauma profoundly affects the sense of being worthy of love, attention and respect, this success is rarely matched by positive relationships with other people.

Disconnection often leads to by isolation and loneliness and shame, and the evidence linking loneliness with serious disease and a shortened life expectancy may be because loneliness is a proxy for trauma.

Shame

One of the ways that people who have experienced trauma, especially abuse, rationalise what has happened is by blaming themselves.

The overwhelming sense of being deeply flawed and unworthy of care and attention makes it very hard to convince people who have suffered trauma that they deserve the care that they are entitled to. They can be very hard to engage with care, and are often excluded because they can be chaotic and have different priorities – safety, money, housing and so on, to clinicians. Self-harm through neglect, and unhealthy behaviours are much more prevalent among people who have experienced trauma, as is more direct self-harm like cutting and suicide.

Fearfulness

Doctors, nurses, receptionists and others who work with people who have experienced trauma and suffer the trauma world that comprises trauma’s aftermath, know very well how overwhelming and contagious patients who suffer severe anxiety can be. From repeat attendances, especially to A&E and out of hours, to panic attacks and aggressive behaviour, the emotional labour, sometimes referred to as secondary trauma, of caring for people who are very chronically, severely fearful is exhausting. A child who has experienced trauma is constantly vigilant, always on edge, prepared for fight or flight at all times. This constant tension and hypervigilance leads to high-levels of hormones like cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline, tense physical posturing or the opposite – cowering; hypertension, breathlessness, chest tightness, irritable bowels; and over time chronic pain, heart-disease and eating disorders – especially when they represent a battle for self-control. The constant fearfulness becomes an inseparable part of the traumatised person’s identity, so that it becomes impossible to relate the physical symptoms to ‘anxiety about a thing’. Somatic symptoms lead to the fear that a fear that there is something wrong, some awful disease in their stomach, chest, brain, or wherever the symptoms are felt. Faced with patients whose anxiety and physical symptoms are overwhelming, clinicians frequently resort to medical investigations, often in a futile attempt at reassurance, to allay their own anxiety or because it’s easier to talk about the diseases they don’t have than the stories they do. Because the risk of biological disease is so much higher for these patients, the tests aren’t entirely without justification, but most of the time they serve to distract rather than reveal the underlying causes.

Feelings of safety, security and trust in other people are laid down in the very earliest years of life. Deprived of this, anxious babies become frightened children and fearful adults. Desperate for human connection, they often make intense attachments with others, and then terrified that they will be broken off, in part because of their own intensity, they sabotage the relationship before the other person lets them down – as has happened so many times before.

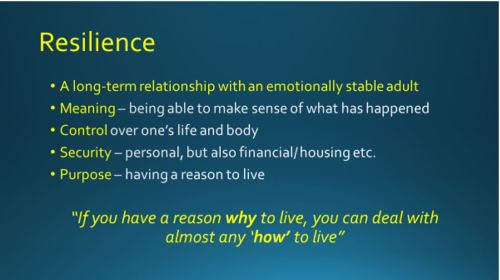

Resilience and protective factors

Because resilience is conflated with moral character- to be resilient is to be seen to be courageous, stoical and strong – the flip-side is that people who suffer more are assumed to be less resilient. All survivors of trauma have have survived by virtue of extraordinary resilience. Those who suffer more, don’t lack resilience,and certainly don’t lack moral character, but suffer more because their trauma was more severe, more prolonged or incurred at a younger age or more vulnerable time in their lives.

Another reason for suffering more is a lack of protective social factors. Almost certainly, but very difficult to prove, the most important is a long-term relationship with an emotionally stable adult. The worse the abuse, and the younger it starts, the harder it is for people to achieve this – an inability to trust other people becomes part of their personality. Afraid that their victims might develop a relationship with anyone else, abusers frequently do whatever they can to stop this happening. Many GPs find ourselves in the position of being the ‘only emotionally stable adult in a victim’s life’. I went for years knowing, or at least suspecting that this was the case before understanding the links with trauma.

Socioeconomic factors can be protective – but only up to a point, as the many survivors of trauma from privileged backgrounds have testified. But severe deprivation can be traumatic in and of itself and exacerbate the effects of other types of trauma.

Trauma in contexts of deprivation may lead to survivors spending their lives being shunted from one crisis service to another, from temporary accommodation to emergency shelter, from one GP to the next. Just as they’ve begun to trust and confide in someone, they are uprooted and moved on. To make matters worse, doctors are taught to be afraid of dependency, to view it as ‘disempowering’ patients, and/ or as a symptom of their own unhealthy/unprofessional need for human connection. Some neglect continuity of care, others actively avoid it. For Arthur Frank, medical sociologist and anthropologist, ‘The structured disruption of continuity of relational care is more than an organisation problem; it is a moral failure of health care, deforming who patients and clinicians can be to and for each other’. In an age where independence and individual autonomy are moral virtues, it is shameful to admit that you need human connection.

Being able to make sense of what happened is often very hard. Abuse is so often done by people who should have provided kindness and protection to a vulnerable young person. It is heartbreaking, but understandable that victims frequently rationalise this by thinking, ‘it must have been something about me, something I did, or said – it must have been, at least in part, if not wholly, my fault’. Abusers sense this and feed into it, telling their victims that they are getting what they deserve until eventually they believe it. Finding different ways of making sense of abuse – perhaps years after it has happened, can be extraordinarily difficult and can require long-term therapy. For some people though, I believe that what happens, over repeated short appointments with a GP, perhaps over many years, is that new narratives are co-created, making sense of what happened in different ways.

Trauma is disempowering; a sense of self control is wrenched, often violently away. Fearfulness and disconnection add to the identity of a body out of control. In abusive relationships the victim is rendered powerless. If the victim is helped to gain a sense of (and of course, actual) control, it helps enormously.

Recovery

Like all healthcare professionals, and especially those who work in deprived areas I care for the survivors of trauma every day. It helps to know as much as possible what evidence there is for recovery.

The slide above is adapted from Judith Herman and Bessel Van der Kolk. It can take years to develop enough trust with a patient to talk about trauma, during which time millions of pounds might be spent investigating and treating their physical symptoms and mental health. The costs to the NHS and other healthcare systems worldwide have never, to my knowledge been investigated. Without the opportunity to develop trusting, long-term, therapeutic relationships, many patients are denied the opportunity of recovery. Van der Kolk warns strongly against assuming that there is ‘a’ treatment for trauma, there are too many different types affecting too many people in too many different ways for one to be sufficient. Because trauma affects both body and mind, treatments that attend to both are very often required. It must also be remembered that trauma is just one of a number of contributory factors to many diseases, and we must not overlook the others, or assume that trauma alone is responsible. Autistic spectrum disorders can be mistaken for trauma because of problems with social interaction, anxiety, sensitivity to sound/ light/ touch and impaired motor coordination are common features of both.

The quality of therapeutic relationship is more important than the type of therapy, but it is almost impossible for the rational self to talk the emotional/ physical self out of its own reality, which is why CBT often fails.

Prevention

Vulnerability to trauma begins before birth and is especially important during the first 2 years of life. Childhood poverty in the UK has been rising for years and is among the worst in the developed world. Programmes to ensure children get the best possible start in life- like Sure Start have been cut or scrapped. Health visitors are completely overwhelmed as are drug and alcohol services. It seems that there will probably be even more victims of trauma in the future. We need to raise awareness among professionals, the public and policy makers. We need advocacy and activism from professionals. We need a social safety net that is not so inadequate that people are forced into destitution or in which a life of intoxication is preferable to the impoverished, hopeless alternative.

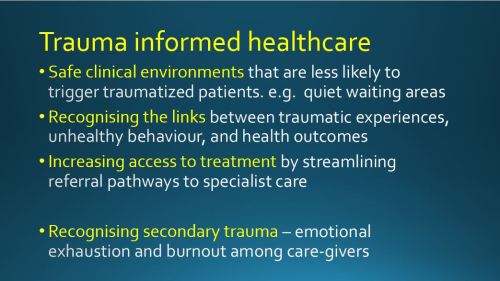

Trauma informed care

Care for people who have experienced trauma needs to be based on evidence and compassion and combined with advocacy and activism

The role of the GP

GPs are not trained therapists, but the work that we do is very often therapeutic. A compassionate curiosity informed by knowledge of the ‘trauma world’ enables empathy, which is described by Leslie Jamison, author of ‘The Empathy Exams’ as, ‘asking the questions whose answers need to be told’.

Treatment begins with the sense of being listened to by someone whose intention is to understand. If the therapist (GP) can take in something of the magnitude of what has happened to the patient, internally and externally, without being totally overwhelmed by it, there is a hope once more of re-establishing a world with meaning in it.

Caroline Garland (2005)

The importance of a containment of this kind cannot be overestimated. In consultations, a therapist is required to take in overwhelming experiences without becoming overwhelmed him/ herself. Profound anxieties and hostility are part of what the trauma patient is unable to hear. The therapist needs to register and contain such feelings sufficiently if the patient is going to come to contain and integrate such feelings him /herself.

This demonstrates that the therapeutic relationship, rather than the event itself is central for the consultation. Joanne Stubley Trauma (2012)

Finally

Learning about trauma has completely transformed my practice, helping me to make sense of so much that has frustrated, worried and exhausted me for years. I am now committed to sharing the lessons with other healthcare professionals, beginning with my whole practice team – from the receptionists who frequently face hostility and unpredictable behaviour, to the secretaries who type reports full of traumatic detail, the nurses who see them for intimate examinations and the doctors who struggle with their inexplicable symptoms. Struggling with patients who have suffered trauma can inflict trauma on those whose job it is to care – both because of the intensity of experiences and because their own trauma may be triggered.

My hope is that the NHS can act with science and compassion combined with advocacy and activism to lessen the amount of trauma being inflicted and improved the care of those who have survived.

Podcast – a 40 minute interview I gave about this subject with some new thoughts, in March 2018 https://soundcloud.com/jane-mulcahy/dr-jonathan-tomlinson-law-and-justice-interview

Further reading:

- ACEs: www.acestoohigh.com

- Trauma informed practice Scotland 2017-8

- Childhood forecasting of a small segment of the population with large economic burden. Dunedin study – Nature http://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-016-0005

- Dunedin study background and commentary https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4412685/

- ‘You should have been more careful’: when doctors shame rape survivors https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/oct/15/obgyn-doctors-shame-sexual-assault-survivors?

- Trauma-centred-care: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/transforming-care/2016/june/in-focus

- Bessel Van Der Kolk: The Body Knows the Score 2015

- Judith Herman: Trauma and Recovery 1992 (2015 edition)

- Daniela Sieff: Understanding and Healing Emotional Trauma 2016

- James Rhodes: Instrumental 2016

- Jay Watts: Borderline Personality Disorder, Why people self-harm

- A Little Life: 2015

- Resilience: 5 minute film: https://vimeo.com/139998006

- Half hour BBC radio 4 programme about adverse childhood experiences: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b070dksr

- Complex PTSD Wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_post-traumatic_stress_disorder

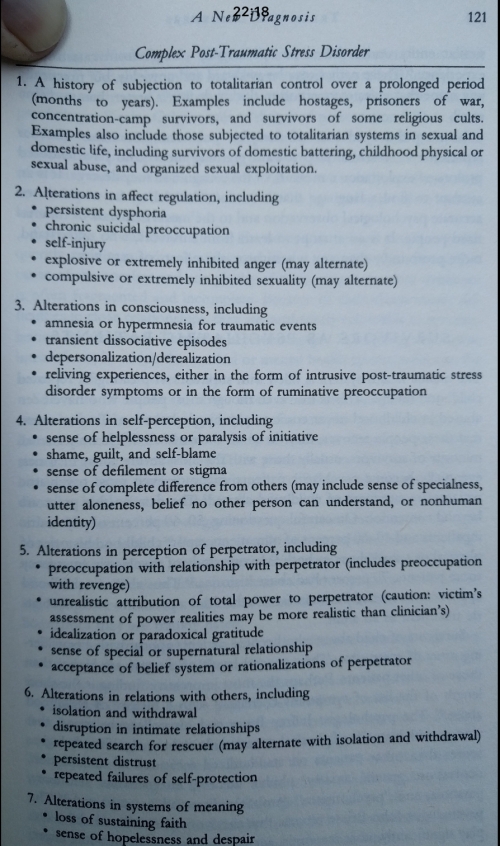

- Complex PTSD – from Judith Herman 1992 – below:

A Gun To His Head as a Child: In Prison as an Adult. NY Times 2017

Reblogged this on Musings of a Penpusher and commented:

A long and worthwhile read – but NOT for the fainthearted.

This is excellent, thank you for such a thorough, detailed post!

Reblogged this on My World, Your World, One World and commented:

Wisdom, necessary information for all who work with other people. Maybe that’s all of us.

Hello this makes a very intersting read, a really comprehensive analysis around the impact of trauma! I have just returned from Toronto looking at LGBTQ mental health and there was much talk about looking at LGBT health issues through the “Trauma Lense” lots of health and community organisations working with LGBT communities having training on trauma informed practice. It was really inspiring! Thank you!

thanks very much. One of my trans patients has described how as a teenager she was really homophobic while she struggled with gender and sexuality in a very macho home culture. She reached out to the trans-community and discovered that in common with a lot of trans adults she was ashamed of her past behaviour – which in turn was driven by internalised social stigma – shame is pervasive and so destructive

When labelling symptoms as due to abuse, be extraordinarily careful you are not infact an abuser.

Labelling a condition that is in fact treatable, that may have an unfamiliar presentation to you as a result of abuse, and stopping the investigatory journey there without thought, perhaps in the face of the patients disagreement is abuse.

It may be caring abuse, as that of the father that beats their child to stop them associating with bad elements, but it is abuse.

It can have serious life-changing and ending consequences.

One case series that spring to mind is https://www.researchgate.net/publication/50908491_Decades_of_delayed_diagnosis_in_4_levodopa-responsive_young-onset_monogenetic_parkinsonism_patients

Always keep an open mind that you may be wrong, and investigate new or changed symptoms.

Thanks, a few people have made similar comments via Twitter and I’ve added a paragraph emphasising the risks. In my experience though, it’s far more common to re-traumatise patients by over-medicalising their symptoms or by failing to recognise their trauma

Great post as usual. I left NHS general practice five years ago after 25 years and now work with Medecins Sans Frontieres. My current mission is in Bangladesh with Rohingya refugees. We are inundated with survivors of acute trauma and provide the only mental health and psychiatric service for half a million displaced people. It’s all rather overwhelming.

As usual you have raised an issue that needs to be understood better, both by patients and clinicians alike.

However, just as you say it is ‘important to remember that the majority of people who have experienced trauma seem to survive without suffering too much.’ it is also important to remember that some people will have chronic pain, medically unexplained symptoms and mental health disorders, who didn’t experience trauma or abuse in childhood.

Medically unexplained symptoms should really be call not yet diagnosed symptoms. The diagnoses could be early childhood trauma, but equally it could be any number of hereditary or acquired conditions such as autism or connective tissue disorders. As Francis above says, to not investigate properly can become abuse in itself; patients that are not believed often end up with depression, exacerbated by pain and other symptoms being left untreated. http://www.clinmed.rcpjournal.org/content/13/Suppl_6/s50.short

I am very glad to see that the RCGP has included Ehlers Danlos in their clinical priorities this year. As Dr Heidi Collins says, if you can’t connect the issues, then think connective tissues. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H0jaF6Rnuv4

Additionally, it would be wrong to rely on the idea that trauma is only caused by abuse. Burke et al. found that children who were hospitalise following a car accident were more likely to develop chronic pain than than children who experience other forms of physical trauma such as planned surgery. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jnr.23802/full

Trauma and abuse is an emotive topic, but if we don’t bring it out into the open then as a society we will never heal. I am grateful to you Jonathon for raising this difficult topic.

thankyou again for a comprehensive and thoughtful post, on an increasingly prominent topic…

The scope of this article is breath-taking. It bestrides the hopelessly compartmentalised domain that is our NHS and invites us to raise our heads and look at the human reality. As a trauma survivor battling neurological pot-holes, ostracism by a hard-hearted family and debt the net that these form needs to be recognised.

Thanks very much – I wrote this with Judith Herman’s discovery that what most survivors want most of all is validation, acknowledgement, respect and vindication etc. There was very little of this in my training or my experience of healthcare, and though I’ve only discovered this after nearly 20 years of practice, I hope to make amends by getting it on the curriculum wherever I can

A very helpful article: I’m not sure about that last slide – Intergenerational trauma can be passed on ‘without them experiencing trauma’. How could that be?

From my ongoing recovery from 3 generations of family trauma going back to 1918 (I’m now 62), I suspect subtle early trauma (14m) on top of poor attachment had a major effect on my resilience… With bad luck and neglect, it then snowballed – repeated different abuses 3, 6, 8…, were then internalised as shaming.

Even though (or ?because) I’m a GP with recurrent burnout, no ‘diagnosis’ of my complex PTSD was made. Another family medic even suggested I might be ‘bipolar’ – ?denial or ‘kinder’ than the real unstable PD label!

So how close do you want to look? For a fascinating study of early impacts,

I recommend: The First Year and the Rest of Your Life: Movement, Development, and Psychotherapeutic Change by Ruella Frank and Frances La Barre, Foundational movement analysis

Thanks very much

Thanks very much – As far as I understand it, intergenerational trauma can be passed on as a result of epigenetic changes caused by the chronic physiological changes wrought by chronic trauma – Bessel Van der Kolk cites research – though it’s early days in so far as evidence goes. Thanks for your recommendation too, I’m running some sessions on ‘wounded healers’ and doctors’ illness narratives next month and this looks very useful,

jonathon

Wow. I coulldn’t read it all in one fell swoop, but will come back to this until I get to the end. Powerful research and writing. My son, ADHD and Asperger’s Syndrome, and I need to take parts of this into consideration.

How do you get help on the NHS for this? I mentioned C-PTSD to a GP and he assumed it meant PTSD. I have finally worked out what has affected me all my life yet I seem ahead of the people around me, even my counsellor who I see privately. And, it could have been different, my mother was told not to have any more children, but she had me, and no one followed that up. She had treatment, tranquillisers, and some kind of doctor but the rest of us had no help living with the unpredictability and frightening behaviour she displayed at home.

There is a great definition of CPTSD which I’ll add to the big tonight, which might help to share with medical professionals

It’s all very new to me, a GP with a lot of experience, who is interested in this area, and grin the feedback I’ve had, it is new to most other medical professionals, so please forgive us for being slow to catch up. My ambition is that the blog post and the teaching sessions I’ve got planned will raise awareness and will be freely shared by patients and professionals with and between one another, jonathon

Thanks, I have been called resilient by GP’s and counsellors alike, I suppose I am so high-functioning and good at masking what I feel that no one else notices. I had a melt down at the surgery a few months ago and that wasn’t even recorded in my notes, I know I wasn’t there for my anti-depressant review, but, I assumed it might be noted down. And symptoms? This year I have had 1 GP suggest it is due to the menopause, which hasn’t started for me yet. It is so frustrating.

AB

You are seeing a counsellor privately, probably because the NHS everywhere is limited in the length of continuous 1:1 support on offer: I have had years of therapy – but this has later been supplemented by overcoming fear and shame to share within groups, both open: like 12 step groups, such as CoDA and closed therapy groups, meditation and spiritual approaches.

Other resources:

http://www.outofthestorm.website

http://www.pete-walker.com offers the following

MANAGING EMOTIONAL FLASHBACKS

1. Say to yourself: “I am having a flashback.” Flashbacks take us into a timeless part of the psyche that feels as helpless, hopeless and surrounded by danger as we were in childhood. The feelings and sensations you are experiencing are past memories that cannot hurt you now.

2. Remind yourself: “I feel afraid but I am not in danger! I am safe now, here in the present.” Remember you are now in the safety of the present, far from the danger of the past.

3. Own your right/need to have boundaries. Remind yourself that you do not have to allow anyone to mistreat you; you are free to leave dangerous situations and protest unfair behavior.

4. Speak reassuringly to your Inner Child. The child needs to know that you love her unconditionally– that she can come to you for comfort and protection when she feels lost and scared.

5. Deconstruct eternity thinking. In childhood, fear and abandonment felt endless—a safer future was unimaginable. Remember the flashback will pass as it has many times before.

6. Remind yourself that you are in an adult body with allies, skills and resources to protect you that you never had as a child. (Feeling small and little is a sure sign of a flashback.)

7. Ease back into your body. Fear launches us into “heady” worrying, or numbing and spacing out.

Gently ask your body to relax. Feel each of your major muscle groups and softly encourage them to relax. (Tightened musculature sends unnecessary danger signals to the brain.)

Breathe deeply and slowly. (Holding the breath also signals danger.)

Slow down. Rushing presses the psyche’s panic button.

Find a safe place to unwind and soothe yourself: wrap yourself in a blanket, hold a stuffed animal, lie down in a closet or a bath, take a nap.

Feel the fear in your body without reacting to it. Fear is just an energy in your body that cannot hurt you if you do not run from it or react self-destructively to it.

8. Resist the Inner Critic’s catastrophizing. (a) Use thought-stopping

to halt its exaggeration of danger and need to control the uncontrollable. Refuse to shame, hate or abandon yourself. Channel the anger of self-attack into saying no to unfair self-criticism. (b) Use thought-substitution to replace negative thinking with a memorized list of your qualities and accomplishments.

9. Allow yourself to grieve. Flashbacks are opportunities to release old, unexpressed feelings of fear, hurt, and abandonment, and to validate—and then soothe—the child’s past experience of helplessness and hopelessness. Healthy grieving can turn our tears into self-compassion and our anger into self-protection.

10. Cultivate safe relationships and seek support. Take time alone when you need it, but don’t let shame isolate you. Feeling shame doesn’t mean you are shameful. Educate those close to you about flashbacks and ask them to help you talk and feel your way through them.

11. Learn to identify the types of triggers that lead to flashbacks. Avoid unsafe people, places, activities and triggering mental processes. Practice preventive maintenance with these steps when triggering situations are unavoidable.

12. Figure out what you are flashing back to. Flashbacks are opportunities to discover, validate and heal our wounds from past abuse and abandonment. They also point to our still-unmet developmental needs and can provide motivation to get them met.

13. Be patient with a slow recovery process. It takes time in the present to become un-adrenalized, and considerable time in the future to gradually decrease the intensity, duration and frequency of flashbacks. Real recovery is a gradual process—often two steps forward, one step back. Don’t beat yourself up for having a flashback.

Copyright © 2009 Psychotherapy.net. All rights reserved. Published September, 2009. If you have comments on this article, please send them to

comments@psychotherapy.net or submit them in our Guestbook.

About Pete Walker, MFT: Pete Walker is director of the Lafayette Counseling Center. He has been working as a teacher and mental health professional for thirty years, and is the author of The Tao of Fully Feeling: Harvesting Forgiveness Out of Blame. He presents on this topic annually at JFK University and has also presented the topic at the 41st Annual CAMFT Conference and several EBCAMFT chapter meetings.

Elaborations of the principles in this article—the importance of shrinking the inner critic, the role of grieving in trauma recovery, and the need to be able to stay self- compassionately present to dysphoric affect, as well on his writings on trauma typology and the role of trauma in codependence, can be downloaded for free from his website: http://www.pete-walker.com.

Yes, luckily enough there is a charity offering counselling for donations, which is how I met my current counsellor. Although I now see them privately. I have never been offered anything by the NHS except anti-depressants and a group thing by IAPT which was horrendous.

This year I read, ‘The Body Keeps the Score’ which led me, indirectly to Pete Walker’s work and Out of the Storm. I have experience of the 12 step association Al-anon thanks to a previous relationship with someone who had a drink problem.

I have also gone some way along the road to training to be a counsellor and experienced experiential groups, and psychodynamic counselling.

I have spent a long time trying to find answers, it is only in places like Out of the Storm and other online groups that I find understanding.

Thank you for your recommendations.

There are a few recommended TED talks Brene Brown has given, I think the Anatomy of Trust is a very useful one to hear, she insists that definitions are important and I agree, otherwise we are failing to understand one another by using big words that mean different things according to personal experience, such as trust.

Thank you for your insights GP survivor, and for this article, whcih I am still reading but I think extremely relevant in my experience as physician looking after a wide range of underserved groups.

This article breaks down key factors of trauma: shame, fear, physical symptoms, ACE study, resilience, use of differing modalities in support for individuals who experienced trauma …thank you & fascinating & educational read. The message I take from this is to continue to be an advocate & actively reach out to individuals who may have experienced trauma, to discover meaning, explore physical symptoms, gain reflection & key relationships for survival.

That’s all too familiar I’m afraid, and I’m sorry.

One problem I find is that CPTSD has so many aspects that we begin with the presenting problems (anxiety, depression, etc.) and then over subsequent 10 minute appointments, perhaps over years, build up a picture, like a jigsaw, that begins to make sense. If we’re both luckily enough to have continuity of care that is. The nature of the electronic medical record means that all the pieces are filled separately and so it needs a commited GP (and Patient) to write a comprehensive summary that’s easily retrievable. Another problem is that there isn’t an electronic code for CPTSD! so I have to use something else and add a free text comment including a link to a summary of relevant features.

Definitely a committed approach required by both. Very disappointing to be asked to leave the surgery as my time was up when I raised the possibility of childhood trauma being linked to a number of physical and mental health difficulties I’m experiencing now as an adult.

This stuff is so important. And heartbreaking. Great post

Fantastic article – thank you so much for writing and sharing

Yes, and…

Moreover, we also need to talk about HOW WE TALK ABOUT TRAUMA.

“Trauma” means “wound”.

The aftermath IS Trauma.

The aftermath of traumatization is trauma.

-and all of it is trauma – the wounds we bear, the wounds in our body n soul, the “thorns in our spirit”.

“That’s not trauma, that’s traumatic” –

Gabor Mate

“In western medicine we incorrectly categorize trauma by what happened – when in fact it is the effect left within us”

-Dr Robert Scaer

“The core experience of trauma is being left disconnected, from self, body, others, and of feeling disempowered”

-Dr Judith Herman

“The diagnostic manual deals in categories, not pain”

-Dr Daniel Siegel

1908 William James who coined the term “Psychic Traumata” likened it to “thorns in the spirit” a poetic description of human experience of living wit h trauma – having been traumatized.

Trauma is the aftermath of traumatization.

We cant change what happened. We can’t changed that we have been traumatized by our experiences.

We can heal our trauma.

Trauma is not what happens to us but what we hold inside in absence of empathetic witnesses.

– Peter Levine

Also being able to separate ourselves [somewhat] from what did happen is part of how we can heal.

Moreover, at social level we need to separate responsibility for what happened from those to whom it did happen.

Conflating act and woundedness leaves that burden on the one we call “victim” – even that term places burden upon them adding to their already burdensome enough burden of helplessness and disempowerment.

We need to lift the burden from those who have been traumatized both responsibility for what happened and the burden of holding within themselves what happened- because we cant deal with the fact that it did.

And we need to take responsibility for that as a society, for that is the only way we will have any chance of preventing it happening to yet more others.

Talking about trauma is one step but only one – by continuing to conflate the act of wounding with the wounds born from the blows we further traumatize – extending it deepening the wounds and that is profoundly oppressive.

Yet, sadly the traumatization continues and the trauma persists and grows because of how we’re treated by “services” – and because of how we talk about trauma.

who wrote this article? It expresses my thoughts on this area so well. But we need to take action to prevent this continuing. We know the risk factors for abuse and neglect just as well as we know the risk factors for cardiovascular disease but do little to pick up on them and nothing to prevent it. If I suspect my patient has a 3% risk of cancer they are seen by a specialist within 2 weeks. If I have a 100% suspicion of child neglect i call and call for help and no one listens. I propose we completely shake up the entire system. call it “prevention of suicide” if it brings in the cash (the politicians think this should involve locking up people with mental health problems, but of course the truth is we need to go back 40 years and stop children from being abused and traumatised to prevent the trauma). it is TOO common and VERY PREDICTABLE and will only get worse as we cut early years services and social services budgets. I think we need to stop being so British about sex. In my opinion every British 6 year old should know, explicitly, that it is never OK for someone to touch a childs genitals and who they can talk to if this happens, and this message needs repeating every year. We also need to somehow help vulnerable parents to be wary of who is with their children/living in the home.

Thank you Jonathan for your great article.

I haven’t quite spend 40 years in practice like you. I am a young 3 years GP in Singapore. This is exactly the work of GPs. Thank you for writing it so well and succinctly.

It is really so hard to even put it in words. Indeed our family medicine training betrays us and we had to learn it the hard way.

Some day i would love to visit you with my team to learn more from you. We are absolutely silent about healthcare advocacy down here due to many factors.

Thank you!

I;ve read this twice now and only recently did I see myself in it all. Raised by a father who was alcoholic (WWII did the damage and my mother) a mother who is a pathological narcissist and three children caught in the trauma of all this, I escaped at 19, but I really never escaped the trauma. It followed me for 5 decades. I have no contact with my mother because she destroys life and I was her primary target. My childhood was one of depression and anxiety, and a bad marriage to another narcissist and drugs continued the issues. I finally pulled out of it (divorce and marriage to a good man for 33 years now) and publishing 6 books, but only until recently, watching a program about young kids depression and anxiety did I see myself and my distorted childhood in the program. And I had 12 years of therapy and my background is in psychology..though I didn’t get a degree). Talk about avoidance and blindness. I am glad that i have recovered, but do we really ever totally recover? Mental health issues that aren’t our own (mother) follow us down the years and pollute our own lives. Bless you for the work you do.

‘

]Jane

Thanks, you a lot, Cz I have found your attempt effective about making people conscious on trauma . It includes almost every important features to broaden outlook of deserving people. Still there are lot of misconception on it: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/turning-straw-gold/201510/five-common-misconceptions-about-trauma

but you have taken a benevolent attempt.

A difficult but needed discussion. thank you for provoking it.

Brilliant summary. As a GP of 30y who has always been interested in mental health I only discovered the depth and extent of all this trauma stuff a few years ago, when I moved to work in a deprived area with huge safeguarding issues, substance misuse, prescription opiate dependence and young women with that awful diagnosis of EUPD. (all in & out of the revolving door of ED and psych, with little but antipsychotics and benzos on offer. I despair….) The more you look for trauma the more you find it and it led me to further study in primary care mental health – fascinating but makes me mad at government and big pharma. Also I cringe at how we treated the ‘ overdoses’ when I was an A&E SHO in the mid 80’s. Thanks for yet another brilliant and insightful article.

Thankyou! As a registered nurse for years – and now as a long term foster carer, I am all too aware of the lack of trauma informed practice in the NHS.

Taking my foster child to the first medical with a paediatrician made this glaringly obvious .

I will talk about trauma and the impact of it to anyone who will listen!

The NHS is even further behind education as far as trauma informed practice goes. Every word of this article resonated with me .

Thankyou again – and keep going!

Keep